In July, Treasurer Jim Chalmers announced an independent review of the Reserve Bank of Australia, and in September, the Bank Review panel released Issues Papers and calls for Public Submissions. The Review Panel – comprising Renée Fry‑McKibbin, Carolyn Wilkins and Gordon de Brouwer. As I said to the panel, I have written it as though writing to Treasurer Jim Chalmers. The closing date was the 31st of October, and because this will make for a long article, I will simply say, what follows, is my submission.

======

Dear Minister Chalmers,

Thank you for the opportunity to contribute to this review of the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Themes

This submission covers Monetary policy frameworks such as adherence to the NAIRU and neoclassical “gold standard” mentality over that of monetary sovereign fiat economies. It covers RBA and Government communications about the Finance Franchise myths on Banking, in general. It is critical of the Board composition based on bias in inappropriate neoclassical education and the selection of business representatives instead of economists trained in the issues of fiat economies. Finally, it reviews the Interaction of monetary and fiscal policy with respect to RBA’s performance in applying monetary policy where fiscal policy is more appropriate. As a former employee of the Reserve Bank, I have some knowledge of the inner workings of the Reserve Bank.

I understand the review of the Reserve Bank of Australia is underway to improve monetary policy and its success at realising its goals, governance by the Board, culture, leadership, and recruitment practices. Such a broad range of objectives has yet to be approached since the smaller incidental 1981 Campbell inquiry and before that, presumably at its inception in 1960.

Curtin

Over the last century, Australia’s Central Bank and economy have undergone many changes. In the previous World War, the Curtin Government asserted Commonwealth power over banking, which led to Ben Chifley’s later decision to legislate to nationalise the banks, effectively asserting Commonwealth control over money and credit as per the Commonwealth Bank Act of 1945. However, such nationalisation was later defeated in 1949, as the book “Curtin’s Gift” by John Edwards says on Pg 141.

“Though the postwar Menzies Government amended Chifley’s central banking legislation to reintroduce a board, the Commonwealth’s last-resort power to direct the bank was retained in the legislation and remains today. The Commonwealth Treasurer has conferred on the bank an independent authority to make monetary policy, but it is a conditional independence to pursue a policy of low inflation, sustainable output and employment growth.”

Curtin had also argued for two other changes,

1. Commit to a full employment policy to improve living standards and raise national development.

2. a floating exchange rate to free Australia from the fixed exchange rate with the British pound

Ben Chifley implemented the Full employment policy following Curtin’s full employment paper being submitted to Cabinet in March 1945. Until the rise of Neoliberalism in the 1970s, unemployment would remain dominately at 2% (notably without substantial inflation).

Unemployment rate and NAIRU

This leads to the Reserve Bank’s first failure, which is its commitment to the NAIRU. Interestingly Albanese’s claim of the Job Summit was to seek a “Full Employment Summit”. But unfortunately, the neo-liberals of both the political Party and the Bank adhere to the conservative myth of the NAIRU. Instead of a NABIER – as a better alternative perspective, the Bank incorrectly suggests we are already “fully employed”. [See Prof Mitchell’s analysis: http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=44910 ] A goal that has been achieved if you conclude ABS measures domestic unemployment, which, as you can see from the graphs and my articles covering what should have resulted from the Job Summit [my article & graphs: https://theaimn.com/stagnating-summits-shortfalls/]. This is why “what gets measured” is essential. I will not go into detail about the shortcomings of the ABS statistics as they are probably already well known, and if not, the article aforementioned herein, should inform you.

Raising interest rates as a strategy to deal with inflations is problematic at best. The link between spending and interest rates is unreliable and unpredictable. Interest rates affect both supply and demand. Economic modelling of “supply and demand” is only relevant to highly atomised markets with many participants, like the primary sector. Secondary and tertiary sectors of the economy follow different models. Changes in interest rates can have a reverse effect on inflation. Higher interest rates only affect people with variable interest rate debts. They don’t affect fixed interest rate debt and people with no immediate financial obligation. Higher interest rates increase the income of creditors and redistribute income to the wealthier, rentier class, exacerbating inequality. Fourth, higher interest rates reduce the incentive to undertake debt and may cause “distress borrowing” to service existing debt or keep businesses afloat. The resulting Ponzi balance sheets do a disservice to the economy, and all of the above, risk yet another recession. The government should be applying fiscal, not monetary, policy to these issues rather than letting the Reserve Bank’s adherence to a disproven NAIRU theory collapse the economy into greater inequality.

FIAT economy

Paul Keating’s floating of the Australian currency in 1983 meant Australia entered a new economic space. We became a monetarily sovereign, fiat economy no longer tied to another currency or a gold standard (which even America had abandoned with the collapse of the Brenton Wood decisions in 1971). The implications of which even the Bank of England acknowledges even if neither our government’s political rhetoric nor Reserve Bank acknowledge. [Bank of England video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ziTE32hiWdk]

Instead of shifting into this new space and engaging with this new paradigm of fiat economies, the neoclassical economic conversation stayed with the decades-old “gold standard” economics model. Still, neoclassical economics guides the decisions of the Reserve Bank’s mission to “pursue a policy of low inflation, sustainable output and employment growth.” [“Curtin’s Gift” by John Edwards pg 142]

Problematically, even Board members of the Reserve Bank need to understand the basics of a modern monetary system. [Prof William Mitchell: http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=49696] The Reserve Bank’s role as the currency issuer for the government has been misunderstood by business board appointees blinded by the tunnel vision of their experience as currency users in the business community.

Most of the Board are business people (five in number), three are neoclassical economists (Dr Lowe, Michele Bullock, & Ian Harper), and Dr Steven Kennedy is economics adjacent given his Doctorate was in the Economic Determinants of Health, which is not precisely about the Banking systems. None of the Board has any formal training in the economics of fiat economies or Modern Monetary economies, although that isn’t to say their experience on the Board has yet to give them insight. Some suggest the RBA is best served with Board members selected based on expertise in modern monetary fiat economics rather than as political appointees because of their relationships with former Prime ministers.

To this day, neoclassical economics still guides the decisions of the Reserve Bank’s mission to pursue a policy of “low inflation, sustainable output and employment growth” but has universally failed to achieve what Curtin & Chifley (and even Menzies) did for nearly three decades.

Banking is widely misunderstood as a heavily regulated franchise industry acting as an intermediary between scarce private capital and borrowers. Modern finance is relatively scarce, and depositors are the source of money supplied to borrowers. [Cornell Law School paper: “The Finance Franchise” https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2660&context=facpub]

Misperceptions.

This is among many common public and media misrepresentations of the banking system. In these areas, it should be incumbent upon the government to educate the public through public broadcasting so that the expectations upon the Reserve Bank are properly evaluated. These myths include:

- Banks can only lend out money they have from depositors.

- Credit is an extension of a money multiplier based on deposit reserves.

- Quantitative Easing is printing free finance into the money supply.

- Federal Treasury deficits are a liability to taxpayers.

At a Keystroke.

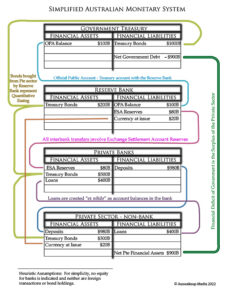

Money in Australia’s economy has two sources. First, that which the Government Treasury supplies through its fiscal agent, the Reserve Bank. In short, that money is spent into existence by the Federal Government. This money is called “Vertical” money, which exists as an Exchange Settlement Account between the Reserve Bank and the Private banks. As the public is not a joint holder of that account, it is not available for lending to the public. Its only purpose is for interbank transactions.

Secondly, a larger pool of credit via lending is generated “ex nihilo” in the economy through private banking, referred to as “horizontal” money. [Also, the Bank of England: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CvRAqR2pAgw] When banks lend, they create deposit IOUs within that bank. Bank’s customer deposits are their liability, and the loan is their asset created by keystrokes. Deposits are fundamentally an IOU from the bank. Similarly, when a bank makes a loan, they generate an IOU deposit for the lender at that bank. The complementary asset for the bank is the loan. Banks create money for borrowers and profit (the interest) for themselves.

Unlike the banking franchise myth, deposits or reserves do not create or limit loans. The perpetuation of this myth in public debate and political pronouncements does a disservice to the public good.

Deposits/Reserves relevancy

Credit creation is simply about a bank finding a credit-worthy customer with whom it can create a digital deposit as an account with that bank with the expectation of future interest payments. The loan to the borrower becomes a bank asset, with an accompanying liability created by a computer entry, which generates the deposit for the borrower. None of the aforementioned Bank reserves is touched, and neither are deposits. The exchange settlement Account reserves are used only when the borrower spends that deposit in another bank. The reserves held at the Central Bank of the lending bank are transferred to the account of the person being paid in the other bank. This is how all bank transfers work; by using the central bank’s reserve accounts.

Instead of adequately describing this in High School and economics education, the government needs to explain how the monetary system works adequately. The government and a properly educated Board of the Reserve Bank need to address these realities.

Regarding my familiarity with this, I worked at the Reserve Bank between September 2001 and October 2002, where I worked on both the operations and technical security teams at the Reserve Bank. In that capacity, I aided reversing the RITS system’s previous outsourcing of AlphaServers operating OpenVMS, previously managed by AustraClear/SFE. Back then, the money churned between banks via their reserve accounts oscillated between $9 to $16 billion daily. The monitoring of that transfer between private bank accounts is the RITS system at the Reserve bank running on an Alpha-VMS mainframe that monitors all account exchanges between banks, which is the system I helped bring back in-house.

Quantitative Easing

In a financial crisis – such as the Pandemic – excessive needs for Exchange Settlement Reserves become evident. The overused strategy of Central banks globally during the Pandemic has been Quantitative Easing. Despite the talk of “printing money”, that is a red herring. Printing money depends on the demand for cash in the private sector – generally around 3% – and never reaches a point where it even approaches a small portion of the digital money supply. Hard currency demand during the Pandemic reached 17%. Digital money is the normality between the Reserve Bank and the private banking systems.

Quantitative Easing affects the money supply by increasing the banks’ ESA reserves at the Reserve Bank. This is done by the Reserve Bank repurchasing Treasury bonds from the private non-bank sector (i.e. pension funds & asset managers) and the private banks. The purchases from the private banking sector rise in digital money extend the ESA reserves. Many private sales of Government Bonds mean more money is circulating in the private sector that may be used to pay off bank loans, reducing the likelihood of borrowings. Technically, increased reserves, while facilitating extensions of interbank transactions, have no direct impact on any credit creation expansion.

Precisely what area of the economy Quantitative Easing serves is also of concern, as “employment growth” wasn’t one of them. The inequality of protecting financialised assets amongst the wealthy ruling class financial markets rather than the working class who lost jobs in the millions. As Adam Tooze, in his recent publication, “Shutdown”, observes

“For the central bank, that meant holding interest rates down. Once again, it came down to financial markets. As far as anyone could figure out, QE worked by driving government bond prices up and yields down. Lower interest rates helped to encourage borrowing for investment and consumption. Lower yields also prompted asset managers to reallocate funds from Treasury markets, where prices were driven up by central bank buying, to riskier assets, like equity and corporate bonds. This boosted corporate borrowing and the stock market. It increased financial net worth and boosted demand.

The supportive cooperation between central banks and treasuries in the common struggle against the coronavirus was thus, the central bankers adamantly insisted, no more than an incidental side effect of their frantic and clumsy efforts to manage the economy by way of financial markets. Despite the relentless accumulation of government debt on their balance sheets, the central bankers insisted that this had nothing to do with financing public spending. Their priorities were to manage interest rates and ensure financial stability, which in practice meant underwriting the high-risk investment strategies of hedge funds and other similar investment vehicles. Rather remarkably, they insisted that tending to financial markets was a more legitimate social mission than openly acknowledging the highly functional, indeed essential role they played in backstopping the government budget at a time of crisis.” [pg 149]

When Financial markets become more important to the Reserve Bank than the well-being of the vast majority of Australians, then the bank’s philosophy is served and managed by too many businessmen & women with a neoliberal ideology to serve the interests of the few above that of the whole economy. As Curtin espoused, the Reserve bank’s original social mission is to “pursue a policy of low inflation, sustainable output and employment growth”. This mission has evidently fallen, by the way, because of the people chosen to run the Board of the Reserve Bank.

Taxpayer’s money?

Finally, It can be demonstrated simply by viewing the balance sheets (irrespective of the accuracy of dollar amounts) of the entities known as

- the Treasury,

- Reserve Bank,

- the collective private banks and

- the collective non-bank private sector

that the federal deficit of the Treasury is the surplus of the Australian economy’s private (and foreign) sector. Deficits are just the government’s way of provisioning the private sector. If a government wishes to pull the spending of an economy back and throttle the growth of an economy, it pursues a surplus for the Treasury, depriving the private sector of funds. John Howard, for example, achieved that when he throttled back the economy to provide the Treasury with a surplus. Consequently, the private sector, desperate for money, borrowed heavily from the Banks. Private debt expanded considerably under John Howard. [See here: https://insidestory.org.au/the-howard-impact/] [or here https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-australia-politics-idUKSYD21821020070508] But of course Mr Chalmers, you should already know this.

Taxpayers are not on the hook for a government’s treasury deficit as that deficit just boosted taxpayers’ finances. The government’s debt is your problem, not ours, since the Treasury and Reserve Bank issue the dollar (which taxpayers don’t because that is a crime called “counterfeiting” with which you would charge us). The currency-issuing government can pay their debts off any time they choose by issuing the dollars to cover them. Admittedly the wedging by political opponents and the Murdoch media would require of this government political courage, not financial inability.

Knowledge is power

The problem is, if submissions for a public review of the functions of the Reserve Bank are to be effective, it is incumbent on the reviewers to have a realistic appreciation of how the banking system works and the Reserve Bank’s role in our financial system. Holding to the public franchise myth, the NAIRU myth, and the Taxpayer funds myth, as many in the media (and possibly members of the Bank Board), will limit the usefulness of any submissions. Providing faulty recommendations to politicians who frequently use the analogy of a household budget to describe how fiat economies work is a recipe for disaster and subsequent legislative policies that will hamper the workings of the Reserve Bank to aid post-pandemic financial recovery.

So we need governors and heads of departments within the RBA who know and understand inflationary causes, recognise the differences between supply vs demand causation and know that raising interest rates is an over-zealous intervention that cures symptoms by killing the patient.

Thank you for the opportunity to submit this letter for your review.

Yours sincerely,

John Haly.

(Auswakeup Media)

[Correction: An earlier version of this article was not “absolutely pedantic accurate” as Inflation from 1945 to 1970 was so small compared to what followed, as to be negligible, but as it wasn’t nonexistent the phrase at the end of the section on Curtin has had the word “substantial” added.]