This is a continuation of my October 2022 submissions in accordance with the review of the RBA announced by Treasurer Jim Chalmers in July. The continuation of my letter to the RBA addresses some of the public’s misperceptions concerning money, banking and the Reserve Bank of Australia. The first part of the letter appeared in the previous issue of Auswakeup, listed as part 1.

Misperceptions.

The issues of monetary approaches to affecting Unemployment and Fiat economies I have previously addressed are among many common public and media misrepresentations of the banking system. In these areas, it should be incumbent upon the government to educate the public through public broadcasting so that the expectations of the Reserve Bank are properly evaluated. These myths include:

- Banks can only lend out money they have from depositors.

- Credit is an extension of a money multiplier based on deposit reserves.

- Quantitative Easing is printing free finance into the money supply.

- Federal Treasury deficits are a liability to taxpayers.

At a Keystroke.

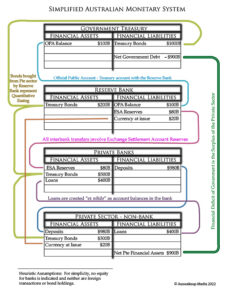

Money in Australia’s economy has two sources. First, that which the Government Treasury supplies through its fiscal agent, the Reserve Bank. In short, that money is spent into existence by the Federal Government. This money is called “Vertical” money, which exists within exchange settlement accounts between the Reserve Bank and the Private banks. As the public is not a joint holder of accounts of this type, such money is not available for lending to the public. Its only purpose is for interbank transactions, as well as the provision of hard currency (coins and banknotes) to banks for servicing the needs of their depositors. Secondly, a larger pool of credit via lending is generated “ex nihilo” in the economy through private banking, referred to as “horizontal” money. The Bank of England has explained this in detail. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CvRAqR2pAgw] When a bank lends, a deposit IOU is created within that bank using digital keystrokes. A customer’s deposit is both the bank’s liability and the customer’s asset. Deposits are fundamentally an IOUs from the bank. Similarly, when a bank makes a loan, the loan contract becomes a liability for the borrower and an asset for the bank. The banks create money for borrowers and also receive profit (in the form of interest) for themselves. There is a common banking franchise myth, that depositors provide deposits to participate in the funding of lending for which depositors receive interest payments for allowing the redirection of their funds. In this misunderstood perspective, the “franchiser” is the Bank assigned the right to market and distribute money on behalf of the depositor. The perpetuation of this myth in public debate and political pronouncements does a disservice to the public good.

Deposits/Reserves relevancy

Credit creation is simply about a bank finding a credit-worthy customer with whom it can create a digital deposit as an account with that bank with the expectation of future interest payments. The loan to the borrower becomes a bank asset, with an accompanying liability created by a computer entry, which generates the deposit for the borrower. None of the aforementioned Bank reserves is touched, and neither are deposits. The exchange settlement Account reserves are used only when the borrower spends that deposit in another bank. The reserves of the lending bank held at the central bank are transferred to the account of the payee in the other bank. This is how all bank transfers work; by using the central bank’s reserve accounts. Instead of describing this process in high schools and economics courses more generally, educational institutions have failed to adequately explain how the monetary system works. The government and a properly educated Board of the Reserve Bank need to address these realities. In regard to my familiarity with this, I worked at the Reserve Bank between September 2001 and October 2002, where I was involved in operations and technical security teams. I aided the reversal of the RITS system’s previous outsourcing of AlphaServers operating Open VMS previously managed by Austra Clear/SFE. At that time the money that churned between banks via their reserve accounts varied between $9b and $16b daily.

Quantitative Easing

In a financial crisis – such as what occurred during the pandemic – it became evident that excessive exchange settlement reserves were needed. The overused strategy of Central banks globally during the Pandemic was Quantitative Easing. The often-encountered talk of “printing money” is a red herring. Printing money depends on the demand for cash in the private sector – which is normally around 3% of the money supply – and never approaches more than a small portion of the digital money supply. Hard currency demand during the pandemic reached 17%. Digital money is the characteristic form of currency used in operations between the Reserve Bank and the private banking system. Quantitative Easing affects the money supply by increasing the banks’ ESA reserves at the Reserve Bank. This occurs when the Reserve Bank purchases Treasury bonds from the private non-bank sector (e.g. bond dealers, pension funds, asset managers) as well as from the private banks, and these purchases increase the volume of ESA reserves. This also means that more money is circulating in the private sector, which money may be used to pay off bank loans, thereby reducing the likelihood of further borrowings. Technically, increased reserves, while facilitating extensions of interbank transactions, have no direct impact on any credit creation expansion. Precisely what area of the economy Quantitative Easing serves is also of concern, as “employment growth” wasn’t one of them. The inequality of protecting financialised assets amongst the wealthy ruling class financial markets rather than the working class who lost jobs in the millions. As Adam Tooze, in his recent publication, “Shutdown”, observes:

“For the central bank, that meant holding interest rates down. Once again, it came down to financial markets. As far as anyone could figure out, QE worked by driving government bond prices up and yields down. Lower interest rates helped to encourage borrowing for investment and consumption. Lower yields also prompted asset managers to reallocate funds from Treasury markets, where prices were driven up by central bank buying, to riskier assets, like equity and corporate bonds. This boosted corporate borrowing and the stock market. It increased financial net worth and boosted demand. The supportive cooperation between central banks and treasuries in the common struggle against the coronavirus was thus, the central bankers adamantly insisted, no more than an incidental side effect of their frantic and clumsy efforts to manage the economy by way of financial markets. Despite the relentless accumulation of government debt on their balance sheets, the central bankers insisted that this had nothing to do with financing public spending. Their priorities were to manage interest rates and ensure financial stability, which in practice meant underwriting the high-risk investment strategies of hedge funds and other similar investment vehicles. Rather remarkably, they insisted that tending to financial markets was a more legitimate social mission than openly acknowledging the highly functional, indeed essential role they played in backstopping the government budget at a time of crisis.” [pg 149] [1]

When Financial markets become more important to the Reserve Bank than the well-being of the vast majority of Australians, then the bank’s philosophy is served and managed by too many businessmen/women who have a neo-liberal ideology to serve the interests of the few above that of the whole economy. As Curtin espoused, the Reserve bank’s original social mission is to “pursue a policy of low inflation, sustainable output and employment growth”. [2] This mission has evidently fallen away, as a consequence of the type of people chosen to run the Board of the Reserve Bank.

Taxpayer’s money?

Finally, It can be demonstrated simply by viewing the balance sheets (irrespective of the accuracy of dollar amounts) of the entities

- the Federal Treasury,

- Reserve Bank,

- the collective private banks and

- the collective non-bank private sector

that the deficit of the Federal Treasury is the combined surplus of the Australian economy’s private sector and foreign sector. Deficits are just the government’s way of provisioning the private sector. If a government wishes to pull the spending of an economy back and throttle the growth of an economy, it pursues a surplus for the Treasury, depriving the private sector of funds. John Howard, for example, achieved that when he throttled back the economy to provide the Treasury with a surplus. Consequently, the private sector, desperate for money, borrowed heavily from the Banks. Private debt expanded considerably under John Howard. [See here: The Howard impact or here: Debt, home repossessions portent for Australia poll]. But of course, Treasurer Jim Chalmers should already know this. Taxpayers are not on the hook for a federal government’s treasury deficit because that deficit just boosts taxpayers’ finances. The government’s debt is its problem, not ours, since the Treasury and Reserve Bank issue the dollar (which taxpayers don’t because that is a crime called “counterfeiting” for which it can prosecute us). The currency-issuing government can pay their debts at any time it chooses by simply issuing the appropriate quantity of currency to cover the debts. Admittedly, the wedging by political opponents and the Murdoch media would require of this government political courage, not financial inability.

Currency Issuing

Many members of the public believe that the issuance of Australian currency is the domain of the taxpayer. Aside from this being the description of the crime of counterfeiting (for which the Australian government would jail any offender), the Reserve Bank definitively sees the issuance of currency as its role. Despite the widely accepted myth about the existence of “taxpayer’s money“, the taxpayer is not an issuer of money, but rather is a user of it. The distinction between a money issuer and a money user is critical to the public understanding of monetary reality. The issuer of a sovereign currency is not operationally constrained and cannot be forced into default in its own currency. However, non-sovereign monetary currency issued or pegged to a foreign-issued currency such as we find within the Eurozone or for the example of Sri Lanka’s debts held in a foreign currency can, of course, lead to default. Australia, like Japan, the U.S., New Zealand and many others, are monetarily sovereign economies with no significant foreign debt and only face the constraints inherent in resource depletion and inflation. Users of Currency are everyone else, including taxpayers, municipalities, and the States and they certainly face monetary constraints. They must earn, budget and use the limited money they can acquire through business, taxation and exchange. Monetary issuers are not so constrained.

Knowledge is power

The problem is, if submissions for a public review of the functions of the Reserve Bank are to be effective, it is incumbent on the reviewers to have a realistic appreciation of how the banking system operates and the Reserve Bank’s role and function in Australia’s financial system. Holding to the public franchise myth, the NAIRU myth, and the Taxpayer funds myth, as many in the media (and possibly members of the Bank Board), will limit the usefulness of any submissions. Providing faulty recommendations to politicians who frequently use the analogy of a household budget to describe how fiat economies work is a recipe for disaster and subsequent legislative policies that will hamper the workings of the Reserve Bank to aid post-pandemic financial recovery. So we need governors and heads of departments within the RBA who know and understand inflationary causes, recognise the differences between supply vs demand causation and know that raising interest rates is an over-zealous intervention that cures symptoms by killing the patient.

Footnotes:

[1] Tooze, A. (2021). “Shutdown: How Covid Shook the World’s Economy.” Penguin Books Ltd. [pg 149]

[2] Edwards, J. K. (2011). Curtin’s Gift: Reinterpreting Australia’s greatest prime minister. Allen & Unwin [pg 142]