The Liberals who cut penalty rates, public services, and taxes for the corporates, have come up with a slogan to replace “Jobs and Growth”. The slogan is, “Let’s Keep Australia Working.”

The implication being a vote for Labor is a vote against your job. The question we need to ask is: “Has the liberal agenda succeeded in keeping Australia working or are jobs and wages diminishing?”

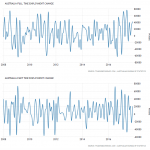

Full-time / Part-time

In October 2017, Michaelia Cash promoted job growth as she claimed “371,500 jobs created over the last year, 315,900 were full time“. Referencing the ABS’s next month’s stats, Malcolm Turnbull later said: “New data shows another 61,600 jobs were created in November, lifting the number of new jobs this year to 383,300.” That may sound convincing and consistent. Of course, as other authors such as Alan Austin note, it is all a matter of strategically timing your announcement, so the figures fit your case. For example, choosing a month where historically low employment featured the previous year to be compared with a better statistic this year. A slightly different choice of month or period produces different results. Statistical variations depend on the accuracy of the collection methods; underlying definitions of employment, and what dates are being compared. The ABS statistical methods for employment issues have come under considerable criticism even from within its ranks. The ABS, although, does not engage in any statistical tampering or deception on behalf of the government. ABS methodology follows the ILO international protocols for measuring unemployment, although the methodology does have its faults.

Monthly deviations in Full-time employment and part-time employment are significant, and cherry picking dates can be misleading. Depending on what is your starting and ending point you can show either rising or falling employment. What is notable is the increasing volatility of employment markets over the years.

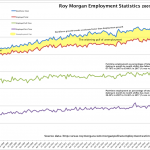

So are there alternative measures which use alternative criteria for measuring employment? Roy Morgan’s measurements are considerably more modest than the ABS stats that Michaelia Cash and Malcolm Turnbull referenced. Their numbers for November 2017 report show long-term job expansion is in part-time jobs, with declining full-time jobs. The figures provided, show that full-time employment decreased 31,000 in the last year till November whereas part-time employment rose by 70,000.

Roy Morgan’s measurements for employment and unemployment differ considerably to the ABS’s methodology for a few fundamental reasons. Morgan’s take on part-time and full-time employment also depicts it as volatile. Morgan shows that part-time employment is growing faster than full-time as the job market is becoming increasingly casualised. A point with which even the RBA agrees. Graphing these statistics over the last ten year shows a clear trend which the ABS methodology obscures while Roy Morgan’s method makes it easier to track. This methodology is also notable for tracking under-employment, or what the ABS calls “hidden unemployment”.

Employment numbers have risen, but so has the total labour workforce seeking or occupying employment. The problem is that unemployment and underemployment according to Roy Morgan’s stats were 2.394 million people in Nov 2017 (18.2%). Combined underemployment and unemployment haven’t been consistently below 2 million since 2011. One has to dig through ABS’s statistics for their underutilisation figures to see a similar pattern. Roy Morgan reports 9.8% unemployment, and for ABS it is 5.4% in November 2017. Using percentage figures in a growing labour force can be inherently deceptive. According to the ABS, our unemployment rate in Nov 2017 is at 5.4%, and the last time it was that rate was in February 2013. But in February 2013, that represented 660,000 people. By November 2017 5.4% is 708,000 people. Taking Roy Morgan’s unemployment figures for Nov 2017, we have 9.8% or 1,288,000 people. The last time we were at 9.8% in a similar period to ABS’s 2013 figure, was August 2012, where 9.8% represented 1,205,000 people. In essence, 5.4% or 9.8% in 2017 isn’t equivalent to 5.4% or 9.8% in late 2012/early 2013. Whichever statistical methodology you reference, our labour market is worse off regarding raw unemployment numbers, casualisation, and volatility than we were under Labor’s administration.

Working Hours

But what about the hours worked by those who are employed? It would seem self-evident that if part-time work was rising faster than full-time, that hours worked would be reducing. It has long been the thesis of writers such as Alan Austin. I took a slightly different track with ABS data and charted hours worked as a function of just those employed, rather than demonstrating as Alan does, that working hours available for the Adult population is decreasing. In spite of how you look at it, it is evident that adequate working hours are less accessible both to employed and unemployed.

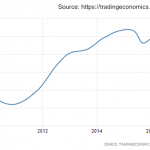

Job Vacancies

Job vacancies in comparison to unemployed job seekers have also been problematic. While there has been a soft rise in vacancies available over time – since the coalition came into power – it has been far below any measure of unemployed numbers (no matter the method). The job vacancy rate for the entire continent of Australia from the government’s IVI index for November 2017 was 177,900. In the four years of the coalition government, it has never risen above 180K and has been as low as 150K. Now to be fair, not all vacancies (although most) advertise online. The ANZ, although, regularly tracks job advertisements saying “Job ads growth was 3.7 percent year-on-year in December, a steep fall from 6 percent in November. In trend terms, the numbers looked a bit better at 4.7 percent year-on-year, but this was down sharply from 9.4 percent annual growth in early 2016.” So let’s factor in these adjustments. Fortunately, Trading Economics has already done this, reporting “Job Vacancies in Australia increased to 201.30 Thousand in the third quarter of 2017 from 189.20 Thousand in the second quarter of 2017“. Despite the increase, 201K job vacancies hardly make a dent in 1,288,000 unemployed people let alone 2.394 million under-employed and unemployed persons seeking jobs in Australia.

Wages

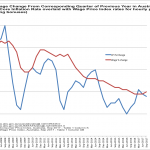

Well, at least the employed get paid, you may – in the resignation of these dismal statistics – sigh. Therein the news gets worse. Wage rate growth continues to stagnate, to levels unseen in this century down as far as 1.9% in the previous quarter. While there is still growth, the question needs to be: Is the growth rate keeping up with that of the CPI? The answer on the surface is “barely”. ABS statistics graphed here show that it is predominately keeping its head above water. The CPI is widely criticised for “excluding home purchase costs“. In a country where private debt towers over GDP by 122% and housing affordability limits access to homes, this is a significant omission. “The ABS does produce cost of living indices which consider the cost of living according to your source of income – wage, pension, or government benefits“, states the Guardian’s Greg Jericho. Once you add the real cost of living factors, you will quickly realise wages are not keeping up with the actual costs of living.

Despite the falling wage growth rates, productivity has been expanding by all indicators. One would assume if the nation is being more productive that wages should rise accordingly. So the claim by the Prime Minister has turned from claiming the lack of wage movement is a function of a lack of security and productivity to being “blamed [for] a lack of economic demand“, despite later boasting about Australia’s economic growth. It would appear the government’s excuses change from month to month and assume nobody is keeping track. So despite fewer hours available collectively for the employed, and reducing wage rises, the level of productivity in the country has been rising.

Job Losses

Job losses for specific industries under the instigation of the coalition will have long-term consequences for our economy. Some of these include:

- Abbott and Hockey’s dismantling of the car manufacturing industry in this country for a preference for imports from China, Korea and Japan saw the end of jobs for thousands of workers with estimates from 90K to 200K losses. Hockey had admitted in Parliament that “Ending the age of entitlement for the industry was a hard decision, but it needed to be made because as a result of that decision we were able to get free-trade agreements with Korea, Japan and China.’’

- The government continues to seek means to support a diminishing mining industry and supply $1billion to Adani Mine. Mining employment is contracting, but it is being promoted at the cost of a tourism industry that employs more than twice the number of people. The tourism sector has the more significant potential for job creation than the mining sector.

- The coalition has overseen one in ten public servants losing their jobs, while spending on consultants has risen by $300 million. Amongst those civil servants, the tax department has divested itself of 4400 employees and their expertise in keeping tax avoidance in check, so private companies could stash money overseas whether acquired via profits or tax cuts rather than use it to employ more people in Australia.

Foreign Workers

There are 37 Visa sub-classes available for a foreigner to work under in Australia of which the 457 sub-class received significant notoriety. As at the end of 2016, there were 95,758 people in Australia who had that visa. That sub-class is being replaced by two separate classes – as announced in April of 2017 – for the future, so tracking worker visas will ultimately be more complex from here on in. Consequently, as a result, the 457 class numbers will naturally begin to shrink which will no doubt be a talking point for the government from hereon.

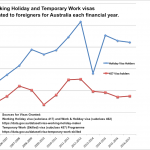

The lessor referenced 417 and 462 Class of working holidaymakers has had 63,988 visitors granted with working rights last year up until September of 2017. Mapping these three visa classes over the last decade gives one a perspective of for whom the government focusses on “keeping working”.

Now to be fair even if all these people left tomorrow it would still not have a significant impact on unemployment and not simply because the numbers are “low” relative to the numbers of unemployed. As usual, it is nuanced, and for a greater understanding, I have written on this at greater length here.

Conclusion.

It is, although, evident that the claims by politicians about their success in managing an economy that has produced employment is highly subjective and lacks credibility. Whatever the coalition is doing, it is NOT keeping Australia working.