The threat of Artificial Intelligence effectively doing jobs has raised fears that tomorrow’s world will be increasingly jobless. There are competing proposals to resolve the societal fallout of a jobless world.

One proposal is a Universal Basic Income (UBI) which entails the provision of a consistent and unqualified monetary allowance to every member of a given society, irrespective of their financial standing, employment situation, or any other relevant considerations. It has had several well-known advocates, from Democratic presidential hopeful Andrew Yang to tech billionaire Elon Musk. Variations on the UBI have been trialled, such as in Finland recently from January 2017 to December 2018, where 2,000 unemployed people in Finland received an unconditional monthly payment of €560 ($634) instead of their usual unemployment benefit. The results were mixed and not the solution people were expecting. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) research on Basic Income holds significant value due to its nuanced and comprehensive analysis of nations that have implemented this policy.

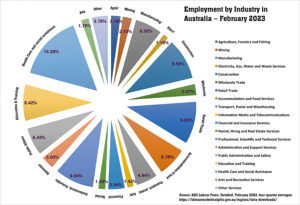

The other proposal is a Federal Job Guarantee. The concept of a job guarantee (JG) is where the federal government provides a publicly financed employment opportunity to individuals willing and able to work but unable to secure employment within the private sector. The government assumes the role of the “employer of last resort,” guaranteeing employment opportunities for all individuals seeking work. The program’s primary objective is to achieve both full employment and price stability to provide a sustainable solution to the dual problems of inflation and unemployment. This is accomplished through the establishment of a buffer stock of employed individuals who receive only the minimum wage. These individuals are engaged in a range of socially beneficial activities, which are determined and organised at the Federal, State and Local levels. Examples of such activities could include infrastructure projects, community services, and environmental initiatives.

This article does not delve into the intricacies of a job guarantee. Instead, it critically evaluates the UBI as the labour market policy of choice. Ten vectors of evaluation are presented within this article.

1. Lack of Inflation Controls and Productivity Enhancement

The absence of inflation controls in a Universal Basic Income (UBI) contrasts with the counter-cyclical nature of a job guarantee. The job guarantee is highly effective in mitigating the adverse effects of deflation and inflation. Therefore, it has been maintained that a UBI inherently contributes to inflation due to its injection of funds to consumers, which is not productivity linked to the economy. An equivalent increase in the production of goods and services does not accompany a UBI. The primary recipients are low-income individuals, as the existing capitalist system has already generated significant inequality. These individuals are more likely to spend the additional funds in the economy but may not contribute to producing goods and services. The prominence of financialisation in economic crises has already led to a rise in debt obligations without effectively enhancing the real economy’s production capacity in sectors that can be used to service the mounting debt. This phenomenon is particularly evident among affluent individuals who accumulate and horde income in off-shore facilities. The provision of income to individuals with low incomes that do not effectively enhance productivity, unlike a Job Guarantee program, compounds these failings. Consequently, this approach may result in inevitable economic price increases, as corporate entities will likely exploit the increased income. This was evident in price gouging long after pandemic supply shocks abated.

2. Reinforcement of Structural Under-Class and Inequity Issues

Universal Basic Income (UBI) fails to promote job preparedness effectively and may contribute to prolonged unemployment. Protracted unemployment presents challenges due to the social and psychological consequences associated with extended periods of unemployment. Peter Warr outlines the detrimental effects on mental well-being, “typically described in terms of increased anxiety, depression, insomnia, irritability, lack of confidence, listlessness, and general nervousness” (Warr et al. Pg. 53). Clinical depression can manifest as early as three weeks, and individuals experiencing it for an extended period may exhibit declining and suboptimal psychological functioning.

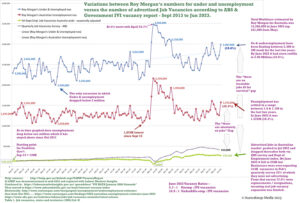

It is worth noting that the government does not explicitly commit to achieving full employment, and even when it does strive for “full employment,” it does so within the confines of the flawed concept that restricts it to the Reserve Bank of Australia’s NAIRU (A predetermined level of acceptable unemployment purported to offset inflation). Parallel to the prevailing circumstances observed in Western societies, this phenomenon forms a hierarchical subpopulation dependent on a governing body’s benevolence, akin to individuals’ reliance on NewStart/JobSeeker in Australia on the “benevolence” of federal governments. The government and media often stigmatise individuals who rely on welfare as NEATS (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) and dole-bludgers, implying that the unemployed have willingly chosen not to seek employment. Universal Basic Income (UBI) aligns with the prevailing neoliberal discourse by acknowledging the existence of structural unemployment and insufficient salaries, thereby perpetuating ongoing inequality.

3. Subsidy for Private Businesses and Wage Deflation

Implementing a Universal Basic Income (UBI) does not exert any pressure on the private sector to enhance wages for the limited number of available jobs. The Job Guarantee compels the private sector to engage in competitive wage offerings to attract workers. On the contrary, a UBI could be perceived as a form of government assistance provided to private enterprises. Companies may reduce their labour expenditures due to the government providing a ‘basic income’. Implementing a UBI can result in wage deflation since companies may exploit this policy to justify decreasing employees’ compensation. Corporations motivated by the objective of increasing profits may promptly reduce remuneration to the labour force to minimise costs associated with their factors of production. Wage stagnation poses a significant concern in numerous Western nations, as the growth of wages has become disconnected from productivity advances over an extended time. Implementing this policy could potentially expedite the “Uberization of jobs” phenomenon since it would substantially subsidise companies. Consequently, employers may experience diminished incentives to provide a salary that ensures a decent standard of living relative to the inflation a UBI would trigger.

4. Insufficient Poverty Reduction and Neglect of Specific Needs

The effectiveness of a Universal Basic Income (UBI) in reducing poverty is not guaranteed, and the potential inflationary consequences discussed earlier could diminish the purchasing power of the income provided. In most nations, social welfare programs are often designed with means-testing mechanisms and are specifically aimed at assisting specific disabled individuals who are determined to be in need. Governments will typically treat Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a financial welfare replacement for targeted welfare programs that specifically cater to individuals requiring costly disability mitigating measures.

The unemployment rates among individuals with Downs syndrome are typically above 80%. A UBI does nothing to encourage them to seek employment opportunities where they so desire actively. A UBI could exacerbate their disability because it is insufficient to deal with needs inherent to mitigate their physical or social disadvantage. The UBI fails to adequately address the intrinsic needs that are more expensive. Inadequate payment will result in a heightened level of relative poverty for the receiver without the alleviation that an individual without disabilities could experience as an improvement to their standard of living. The long-term sustainability of an inflationary Universal Basic Income (UBI) is doubtful, even for those without disabilities. The UBI is not a poverty buffer stock like a Job Guarantee. Although not as significant, it can have implications for some income groups since it may result in a movement of individuals within higher taxation thresholds.

5. Lack of Dignity and Meaningful Engagement

6. Unconditional Income and Its Effects on Job Market

7. Psychological Benefits and Social Well-Being

Psychological benefits can be associated with active participation in a Job Guarantee program, which entails providing community-based employment opportunities sponsored by the federal government but deployed at the state and local levels. It can be tailored to the talents and preferences of the individuals involved. A paid, personally rewarding and socially appreciated job offers psycho-social advantages that a UBI cannot supply. When individuals are left to rely solely on their own resources and have minimal financial means, even though it may enhance their ability to survive, it may not enhance their willingness. A UBI without work can also contribute to a social disconnection that increases the likelihood of engaging in a lack of self-worth and drug and alcohol misuse. Engaging in regular job duties within a professional setting mitigates these challenges and fosters an enhanced perception of personal value, a facet that is not achieved through implementing a UBI.

8. Hobbies vs. Contributions to the Community

The concept of work pertains to activities performed on behalf of others, while hobbies refer to activities pursued for personal fulfilment. The proposition of utilising Universal Basic Income (UBI) to finance one’s pastime is argued by some proponents. It can be contended that this approach fosters self-indulgence without necessarily providing individuals with sufficient compensation for their societal contributions. Implementing a job guarantee program involves individuals in significant community initiatives, as the employment opportunities are specifically designed and executed within the local community context. Work is a contribution that has the potential to offer meaningful work opportunities, even to individuals who may face disadvantages. Various social enterprises, like Anglicare, Big Issue, Endeavour Packaging, and Clean Force Property Services, among others, exemplify these opportunities. The effectiveness of a UBI in facilitating socially inclined individuals to participate in beneficial community activities in a financially feasible manner will be contingent upon their capability, stability (both financial and otherwise), and inclination. The convergence of these characteristics to promote the societal benefit of UBI is expected to be more limited than normalised.

9. Dependency on Government Goodwill to address Inequity Issues

A Universal Basic Income (UBI) relieves the central government of its need to ensure substantial work opportunities, instead relying on the government’s benevolence to sustain fair payment levels to alleviate poverty. An analysis of the NewStart/JobSeeker program, pensions, and other social payments reveals a lack of willingness among Western governments to adopt these measures. The UBI has limited efficacy in addressing social and financial inequities due to its constrained potential for productivity growth, inflationary implications, and the potential for social exclusion. Moreover, there is a significant probability that the UBI may be implemented at a level below the poverty line, as evidenced by numerous existing welfare programs.

10. Universality versus Dignity-based income.

One of the primary contentions against implementing a UBI is providing financial resources to individuals who don’t require it. Instead of advocating for universality, it is argued that the provision of any basic Income should be subject to limitations. By implementing a “Dignified Basic Income” (DBI) primarily aimed at individuals who are physically or psychologically unable to engage in employment, the program can effectively prioritise assistance for those most in need of a social safety net. This focused strategy guarantees that resources are allocated to individuals with authentic requirements, hence diminishing income disparity and augmenting the overall effectiveness in mitigating poverty. By directing attention towards a Dignified Basic Income aimed at persons unable to participate in the workforce, it becomes possible to enhance the program’s cost management efficiency and ensure that resources are allocated to those who require them the most. Implementing this focused strategy enhances the program’s long-term sustainability by allocating resources towards individuals with distinct needs. This category encompasses those who experience severe disabilities, chronic illnesses, or other problems that impede their ability to engage in conventional forms of employment.

The proposition of a Job Guarantee or “Employer of Last Resort” (ELR) program is frequently advocated by heterodox economists to achieve complete employment. A DBI program designed for individuals who are physically or mentally unable to engage in employment can be a valuable addition to such a scheme. An accompanying focused DBI acknowledges each person’s inherent worth and significance, encompassing those unable to participate in employment. One potential benefit is the mitigation of social stigma commonly linked to receiving unemployment or disability benefits. The promotion of inclusion and compassion within society can be achieved by providing a decent income to individuals who cannot engage in the job market owing to actual constraints. Job Guarantee is for involuntary unemployment. It is imperative to establish a clear distinction between incapacity and unwillingness. A social welfare program such as a DBI should not be designed to support those who, of their own volition and without any mental internal or external constraints, opt in a parasitic manner (as might be typical of the leisure class ) not to seek employment. This is yet another reason it should never be “Universal”.

Conclusion

Numerous esteemed individuals have passionately advocated for the potential benefits of introducing a Universal Basic Income as a viable remedy for the inadequacies of Newstart/Jobseeker and other subpar welfare initiatives. The objectives for these actions are rooted in progressive agendas that aim to address poverty and uplift individuals from the lower echelons of society. The objectives and devotion to the larger societal welfare are deserving of applause. There is a valid argument in favour of advocating for the augmentation of Newstart/Jobseeker allowances and social welfare payments and the reduction of substantial subsidies provided to wealthy people to foster a more resilient labour market. Nevertheless, asserting that a Universal Basic Income is how these objectives may be securely accomplished is a formula for disillusionment.

—-//—-

Journal References:

Warr, Peter, et al. “Unemployment and Mental Health: Some British Studies.” Journal of Social Issues, vol. 44, no. 4, Jan. 1988, pp. 47–68, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1988.tb02091.x.