When we contemplate great evil, who comes to mind? Genghis Khan, Vlad the Impaler, Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Pol Pot, Alexander the Great, Attila the Hun, Idi Amin, Kim Il Sung, Josef Mengele, Saddam Hussein, Emperor Nero and so on? Too easy. The reasons are apparent, the history unrefuted and the weight of affirming opinions near universal.

We all like to think of evil as insidious, intentional, cruel, focused and malodorous even. Isn’t “evil” patently recognisable by its social maladjustment? That is the comfortable illusion of how “good folk” describe evil to distinguish ourselves from it. So it may be surprising to hear that according to psychologists nobody thinks of themselves as evil. We self-justify actions and beliefs. Folks may hold their irrationality within their mindset, as they persist with the delusion of being the good guys.

Hitler, for example, grew up in a time where he experienced the open expression of anti-Semitism. He didn’t create anti-semitism, it was his honest belief, that the Jews were responsible for the economic hard times of other Germans in the post-war years. Seems almost banal, doesn’t it?

Chase Replogle writes “Arendt coined the phrase, the ‘banality of evil.’ You can define banal as, ‘so lacking in originality as to be obvious and boring.’ What Arendt observed was that evil feeds not just on extremism, but just as frequently on our banality. Sin works its way deepest into the most boring and apathetic lives.”

We often don’t recognise evil amidst banality as it is human nature to separate “evil” from our apathy, ignorance, “benign neglect”, “thoughtless bureaucracy”, or our an innate desire to please our perceived “superiors”. Aren’t we all just inclined to follow orders? Resistance is hard, besides “who has the time to protest”? Perhaps you vote for the good guys (however or whomever you decide are the “good guys“), and in that single choice, you make once every three years, some may consider their duty complete. “That’s a democracy“, you cry. As though to comfort ourselves we say, “I’ve done the right thing; I’m not evil or fascist!”

Last century’s Version of Fascism

But then who is fascist? Is it what it was or what it will be? How often do we accuse the comparative justification of calling the alt-right “fascist” as being too radical? “Nobody is exterminating minorities in gas chambers” one may say defensively. But recall that Hitler took seven years to bring Germany to war. When was it a step too far?

- When he was promoted to Chancellor on a minority vote in a democracy?

- When he consolidated the Nazi Party’s control of Germany and secretly rebuilt its army from 1933 to 1935?

- When he only talked for years about the possibility of expelling Jews and removing their civil rights?

- When he was objectifying women as subservient for reproductive purposes with no place in key influence roles?

- When he disengaged from the Treaty of Versailles in 1936 and war-tested his military in the Spanish Civil War?

- When he shifted non-german foreigners and Jews into gulags or race specific ghettos?

A thousand banal little steps were undertaken in the decade after the Nazi Party grew from 12 seats in the Reichstag to 107 seats in 1930. By the 1940s his troops were frog-marching across Europe and throwing people into gas chambers. When would you have stopped him or protested or objected in that decade? Neither current parties of the Australian nor American government have been in power as long as Hitler before the war (Jan 1933 to Sep 1939).

When I raised a draft version of the above paragraphs in social media, I was warned, “I think comparison with the holocaust needs to used carefully. The Germans did not just “go along” with the Nazi’s they fought against them until a police state was imposed upon them – while most of the political class stood by till it was too late.” This statement, although, was not entirely valid, as the elite of German society did embrace Hitler enthusiastically. While it is true that some “good” people resisted fascism, as they do today, many others, including Jews didn’t realise the consequences. Irrespective of resistance or because of obliviousness the Nazis still marched across Europe, so perhaps it is a moot point. Contemporaneously the problem is, as always, identifying how fascism has evolved. This awareness is painful for many, as they only want to recognise it in the form it took 80 years ago.

This Century’s version?

Despite refutations of such positions, Perhaps because that was before your lifetime and people are so more “woke” now, it is all very different. So let’s explore into what it may have evolved. Have your responses evolved?

- Did you react when Donald Trump seized power via the electoral college on the votes of a minority?

- Did you respond when Trump began to refocus on the military?

- How about when he spoke of expelling Mexicans and Muslims?

- Did his objectifying of women whom he grabbed by the pussy upset you?

- Did launching air strikes in Syria or breaking established treaties caused you concern? Paris climate accord, Iran Deal, TPP, or NAFTA?

- Did locking children in Gulags and separating many permanently from their parents, upset you?

Australian wannabe

OK, so perhaps America has dysfunctional parallels, but we in Australia are markedly different some may claim.

Our politicians are more subtle and more sophisticatedly communicators than Trump. Still, what were your responses in these circumstances?

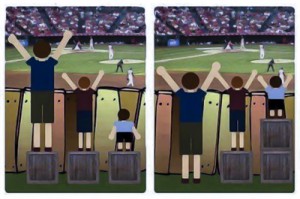

- When 41.8% of all voters voted for the coalition in 2016, did you defend and justify the preferences system for its selection of what the majority wanted?

- When Abbott started spending billions on faulty American aircraft, late running Submarines and involved us in America’s pointless Syrian war, did our propensity for violence concern you?

- When the social dialogue about banning Muslims entered the political fear mongering, did you speak in defence of the vast majority of adherents to a peaceful religious code?

- When misogyny became a familiar and recognisable feature of legislation and leadership, did you say this went too far and defended women?

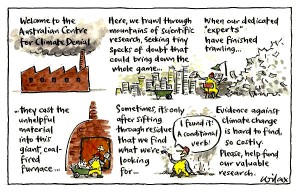

- When Indigenous treaties were scrapped, and political impetus arose that sought to have us withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement were we at all surprised? Did Morrison’s undermining of Refugee Convention obligations, all while adding to our refugee push-factor in bombing raids in Syria, cause alarm?

- When we against any decent moral code not only locked innocent adults and children in gulags for the “crime” of being foreign and desperate but then began actively resisting efforts to provide medical assistance to children, did any sparrows die?

Policies for the people?

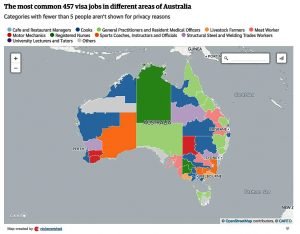

On such subjects, the coalition argues that we need secure border protection for an Island like Australia with minimal 150 km of sea between us at the tip of Queensland and Papua New Guinea to fight off refugees. Even though the majority of refugees fly in and by-pass our secretive “on water matters” border protection. There are many absurdly opposing arguments, such as desperately trying to entwine refugee policy with the war on terror. Money, alternatively, is unavailable for the likes of education, health, social and legal justice, wage equality, mediocre wage growth and affordable housing, utilities food or justice. This absurdity of fearmongering about refugee crime suggests we need be strong and prepared for an invasion of terrorism in our population but simultaneously drives policy to make our community uneducated, poor, unhealthy, un-housed, oppressed and socially divided.

So just because we can see the correlation between what we thought was the progress towards evil and contemporary examples of the same, does it mean we should rethink real “evil”? I mean, we all accept that these things happen in society. Unfortunate, perhaps, but “evil”. Let’s try to compromise surely. “We are doing this for your security and to save you from the threat of terrorism,” says our politicians. “You will hardly notice it”, they say. Moreover, that last part is right. Like the gradually heated frog in the pot you don’t mainly notice it, and by the time the pot boils, it is way too late.

What we don’t discuss over dinner

“Isn’t that politics”? “I’m not political”. “I disengage from that stuff”. What was it Martin Luthor King said? “All that needs to happen for evil to prevail is that good men do nothing.” Do we by our silence, allow all of that to happen? Perhaps we are too busy to notice the correlations, too compromised by our selfish preoccupations, perhaps we don’t care. However, surely that isn’t bad. Surely that isn’t “evil”.

Amidst the same social media post commentary I previously referenced one gentleman wrote “most people aren’t evil just caught up in their own lives… “ and in this contemporary society this is, unfortunately, both accurate and a misconception.

Distractive Accuracy

“Accurate” because of our history of

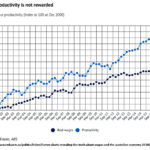

- deregulation of industrial relations has meant more extended unofficial work hours and strangled wage growth,

- financial deregulation, negative gearing, foreign investment and Capital Gains Concessions has blown out mortgage costs

- Privatisation and deregulation of Education has made higher education expenses and debt-ridden

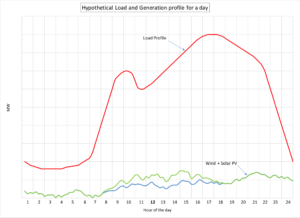

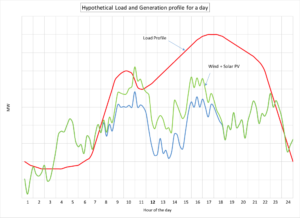

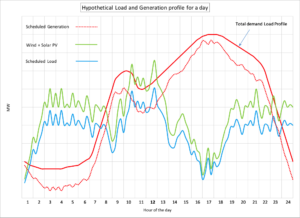

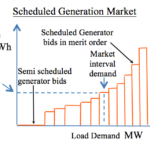

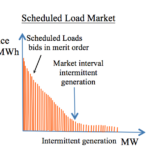

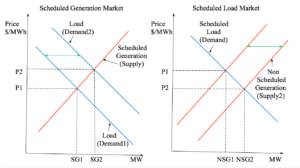

- the privatisation of energy provision, scheduled generation markets and resistance to renewables have resulted in larger utility bills increasing household debt.

Being “caught up in our own lives” is true because of more extended hours with reduced skill sets for less pay and bigger bills. These are the results of deliberate bi-partisan political policy choices. We should never forget that policies designed to redistribute wealth upwards, increase inequality, engage in a civil war on society using the tools of racism and attacks on a range of marginalised groups, have a deliberate purpose.

Misperceived evils

A “misperception” because as an act of self-protection of ego, we protest that we are not evil, just a little compromised, more compliant, obedient or scared of being socially ostracised, perhaps?” As I said before, evil is integral to life’s banality; it is everyday ordinary barely conscious choices we make. It exists in the tiny, tired, “I don’t have the time“, “it’s not that bad“, “there are worse situations” excuses we tell ourselves to support the choices we make. Evil is not in the individual decision but the cumulative. It takes thousands of bad collective small choices made over years, that lead to the exclamation of “how the Fu€ did we get here?” as we watch border patrol march down our streets, while our “authorities” detain and abuse our children and bash our disabled neighbours.

Worry not, you’re safe!

But fret not, if you never raised a voice in protest, then they are unlikely to arrest or hamper you because you played it safe with your daily banality. You remained silenced by indecision and compromise; you respected authority and the status quo; you defended the need for thoughtless bureaucracy and realised it was too much work to improve your knowledge of history and politics. Besides, our administration is acutely aware from their study of your metadata, your phone messages, your facebook posts, and even your TV set-top box that you’re still compliant, malleable, cooperative, collaborators but never, really, truly, magnanimously, unambiguously … “evil”?