Was Banjo Paterson’s 1889 poem “Clancy, of the Overflow”, acknowledging a country of flooding plains? In not, Dorothea Mackellar’s “Sunburnt country” was in her 1906 poem about “drought and flooding rains”. Floods have long been a dominant feature of the Australian landscape, so much so, that “100-year floods” have been featured in recent decades every half dozen years or so. The apparent expectation of a lead-in like this is it’s a conversation on climate change. But, seriously, so many scientists and meteorological experts have spoken of this ad nauseam (see the 6th IPCC report). There is not much this journalist can add to what’s already been said. The latest flooding on the Eastern coast of Australia speaks volumes. Ignoring the need to mitigate Climate change has only two protagonists.

-

Attitudes to the Flood Crisis show the contempt with which Rural Australians are held by former Liberal Party president. The most recalcitrant of ideologues in media and political circles who are bribed by corporate lobbying of fossil fuel interests or

- The psychologically stunted individuals are driven by a Dunning-Kruger misperception of their intellectual incapacity.

So if you fall into one of those categories, I will not waste time addressing your issues.

Climate change has created two very typical states of environmental disasters in the Australian landscape. Fires and Floods! The rescue of Australians from either disaster has different primary responder workforces.

Fire Management

Fire Brigades in Australia, began in the NSW colony in 1820, consisting of soldiers trained to use fire fighting appliances. By 1836 the Australian Insurance Company established a Fire Brigade, manned by local volunteers with buckets, ladders and axes. By 1884 the Fire Brigades Act created the Metropolitan Fire Brigade. By 1910 that Act was extended across the NSW state. In 2011 that Fire Brigade became known as “Fire and Rescue NSW”. Nowadays, paid professional and volunteer fire fighting bodies are funded in every state. However, the NSW fire mitigation bodies suffered significant funding reductions in the years leading up to the 2019 fires. Gladys Berejiklian’s government instigated the cuts, but only the alternative media outlets covered this failure of oversight and management.

Flood Management

Flood management, on the other hand, had an even poorer history. European settlement in New South Wales recognised the risk from the flood hazards as far back as 1788. However, the 1810 Hawkesbury River flooding and 1867 floods of Pitt Town and Windsor, resulted in differing strategies by the colonial government. By the 1870s, volunteer ‘water brigades’ arose. This, in time, developed into the State Emergency Service (SES) in 1955. The only professionally paid body associated with flooding is the Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology. The under-resourced original SES had no mandate for Flood mitigation. It was not restructured till the emergence of the State Emergency Service Act 1989. Chas Keys, the Deputy Director-General, NSW State Emergency Service, wrote in a paper in 1999:

“Half a century ago, the management of Australia’s most serious natural hazard was very largely a matter of community self-help. Science was not brought to bear, there was little or no prior consideration of potential ways of handling flood problems, and the government was barely active except in after-the-fact relief endeavours.”

While Chas Keys claimed this had changed, recent events demonstrate effective real-time flood management still eludes the government and SES. The SES is still dominantly a volunteer organisation covering a wide range of emergency scenarios from fire, storms, floods, road crashes, as well as alpine, bush & abseiling search and rescue. There is training nowadays for all of these events, but it’s largely dependent on individual interest from the volunteer. At the end of 2018-19, NSW SES had a full-time equivalent workforce of 352 staff but 27 times as many volunteers.

Government reluctance

The State and Federal Government’s response to cries for help by flood victims has been woeful. The Federal Government, in particular, has demonstrated a consistent reluctance to step up, in any emergency, whether that be a pandemic, economic recession, bushfires or floods.

The Liberal Party’s previous reputation of being notoriously marred by climate-denying recidivists manifests as a reluctance to admit the consequences of Climate Change. So there is a foreseeable reluctance to acknowledge the existence of the symptoms. This follows a consequential hesitancy to act quickly to mitigate a flood crisis. Hence the slow and reluctant response from the Federal Government to the current floods. Considering the American experience of harsh public criticism of George W Bush over Cyclone Katrina flooding, the even slower response by the Australian Government draws understandable outrage. As does the continued reluctance to spend emergency funding of around $4.7 billion sitting idle in the bank! While eventually the ADF was assigned to the task, the perception of their commitment to the flood victims was marred by the need to create photo ops and filmmaking. This only drew further enragement on social media.

Army not trained

Beyond the SES, the Australian Army Reserves have been solicited to provide community aid during the 2010 and 2011 floods. ADF Reservists called upon to assist communities during a flood crisis is problematic, because, as David Littleproud claimed, ADF personnel “aren’t trained in the immediate response”. Still, Army Reservists are called upon more frequently to assist in fire, flood and pandemic situations as they did during the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season. But the reference to a lack of adequate training was implied by the ADF’s flood response in 2022. ADF emergency support was marred by a week-long delayed response and the apparent order to conduct photo ops and training films many saw as a priority above saving lives. The Defence Force’s defence of their filmmaking drew further enragement on social media, but few stopped to query why the defence force thought the training was needed.

SES not ready

The SES found themselves battered by a “natural disaster of unprecedented proportions” and subsequently demonstrated they were under-resourced and overwhelmed. The capitulation of government to reliance on volunteers to respond to natural disasters was admitted to by Premier Dominic Perrottet on Tuesday the 8th in a Press statement. Perrottet acknowledged people felt let down by emergency services, overwhelmed by the scope of the crisis.

If the Federal & State governments, SES and ADF are not up to the task required of them, for whatever reason, legitimate or otherwise, perhaps we need a more focussed body to deal with floods. Although, there is no dedicated, professionally paid specialist “Flood Brigade”, despite flooding being an interstate issue of significant frequency, resulting in large scale relocations, property damage, and even deaths.

Once in a Century?

The history emerging in the 21st century, complete with lives lost, began in the 2007 Hunter Valley/Maitland and Gippsland Floods. This was followed by the 2011 Queensland floods and again by Victorian Floods, till finally later that year, Gippsland again. A year later, in 2012, Eastern Australia and Gippsland suffered floods between February and March. 2013 saw Eastern Australia Floods in Queensland and NSW. While we got a break in 2014, 2015 saw Hunter Valley/Central Coast/Sydney Floods and South – East Queensland, in which 13 people in total died. Tasmanian Floods in 2016 only killed three, and one died in the Central West and Riverina Floods. After the Western Australian Floods of 2017, Cyclone Debbie caused flooding in Eastern Australia. Townsville floods in Queensland killed five people in 2019. Tropical Cyclone Damien in Karratha in 2020 caused flooding in NSW, but it was one of few floods where there were no deaths (although plentiful damage).

Such good luck wasn’t maintained the next year when widespread flash flooding across Gippsland in 2021 killed two people while 200 homes were evacuated in the Latrobe Valley. That flooding occurred only three months after widespread flooding in the Sydney basin, and the Mid North Coast of NSW had already killed three folks.

In 2022 Australia’s Eastern coast has been inundated with rain, and the current score – as of writing – has been 21 lives between Queensland and NSW. New South Wales Premier Dominic Perrottet described the extreme weather as a “one-in-a-one-thousand-year event“.

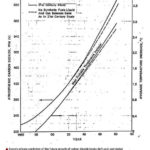

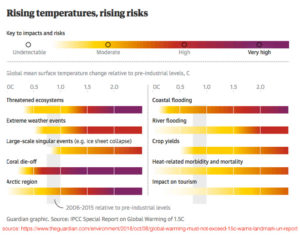

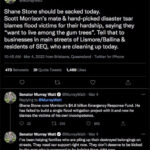

Describing these floods as the one-in-a-one-thousand-year event (or “one-in-500-year” as Morrison did in Lismore) is not only wholly delusional and contrary to every scientific flood report, but also contrary to the lived experience of Australians seeing floods occur year after year. For example, with extensive Brisbane floods increasing in frequency from 1974, four lives were lost, and some 8,000 householders were affected. From 2011 and on to 2022, the comparisons are startling, given all the flood mitigation work done in between. As for Shane Stone, the disaster relief chief and head of the National Resilience and Recovery Agency blaming the victims for their choice of residency, that says much about Morrison’s hand-picked disaster tsar.

Politicians depicted this as a once in a century event, only to experience more in the coming years, stretching their credibility and the public’s resilience with each flood.

Who’s to blame?

Some elements of the government have been prepared to acknowledge how “unacceptable” emergency flood response has been. Others, especially in the Federal Government, are looking to direct blame elsewhere. Blaming the Bureau of Meteorology for an inaccurate forecast only gets you a day’s grace, not a whole week. These disasters have been consistently predicted. The Australian Rainfall and Runoff report: “A guide to flood estimation” notes on page 22:

“There is also mounting evidence that longer-term climate processes also have a major impact on flood risk.”

It goes on to describe La Nina events and interdecadal pacific oscillation, and after “investigating a range of sites in NSW”, it found floods were 1.8 larger than “normal”. (see the report page 22 for a more nuanced explanation of “normal”) Notably, Wilsons River flooding to Lismore in 2017 has no specific mention in the report, unlike the Hunter, Clarence and Woolomombi because most of the data relied upon only extends to 2015. While this report has some 2016 updates, its release in 2019 does not mean the fallout of 2017 mass flooding is included. It may be time for a revision in 2022. That said, making excuses for why we were not ready in the face of all this data – including all the reports preceding the 2022 IPCC report – is a little pathetic.

Alternative?

As the existing system doesn’t work and will become increasingly dysfunctional in the future, we need a complete regime change. Volunteers in Fire Brigade, SES, and Army Reservists (some of whom operate in a mix of either, some or all services) should continue as separate entities. Given that these disasters cross the State lines, funding should be federal at all levels. The temptation for tight budgets at State levels to be a reason to cut back on these services, should be dissuaded by shifting these to a federal responsibility. Professional crewed Fire Brigades and Flood Brigades bodies to manage mitigation, rescue, and recovery for these disasters need launching! It should transition all current State-based professionals. These brigades’ immediate responses should be based on predictive science measuring environmental changes and preparing for the worst.

To have these federally funded bodies respond to these emergencies far faster than this government and ADF have reacted to people in need in Lismore, Coraki, Girards Hill, Southgate, Mullumbimby, Picton and many others, we need one more change. We need a federal government that will not simply announce its intentions without any measurable, functional outcomes or run off overseas or hide from public scrutiny, but act promptly to produce results in infrastructure and finance in the towns that will preserve our communities. But, unfortunately, that government is not our current incumbent, whose leader only now, weeks after the start of the floods, while visiting Lismore, indicated an “intention” to declare a “State of Emergency”.