The popular framing of macroeconomic topics in the media stems from a recurrently misguided “common sense” intuition. It is articulated through erroneous hearsay between mutually uninformed individuals. Public economic notions are susceptible to socialised norms of popular associations, like comparing a federal budget to a household budget. The embeddedness of such illegitimate framing makes more accurate reframing challenging. For example, the negative association of a “deficit” tends to overwhelm the accounting reality of its balancing “surplus”. Assets may balance liabilities, but the latter’s negativity draws the focus. As such, few consider that a “government deficit” necessarily means someone else’s surplus. Equally problematic are terms like “taxpayers’ money” for financial assets for which they have no liability. One should be aware that possession or presumed “ownership” doesn’t correlate with creation or liability. Yet “taxpayers’ money” is frequently misused to imply such correlations. With these points in mind, let us examine the economic implications of the phrases “government deficit” and “taxpayers’ money.”

In discussions of money, production and liability are often neglected, even though the issuer and associated liability are explicitly indicated on our currency notes. Orthodox economists frequently equate possession with ultimate liability. This led to the erroneous assumption that money is a product of market activity. Myth makers employ a classical fairy tale originating from Adam Smith to accomplish this — that money originated from barter markets. Anthropologists have consistently refuted this fallacy. Oscar Soberg, citing David Graeber’s book “Debt”‘s quote from Prof. Caroline Humphrey, notes: “No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing.” (Soberg, 2022). Despite the evidence collected rationally and methodically by anthropology, the unfounded myth of barter is repeatedly presented in the introductory chapters of orthodox economics texts worldwide.

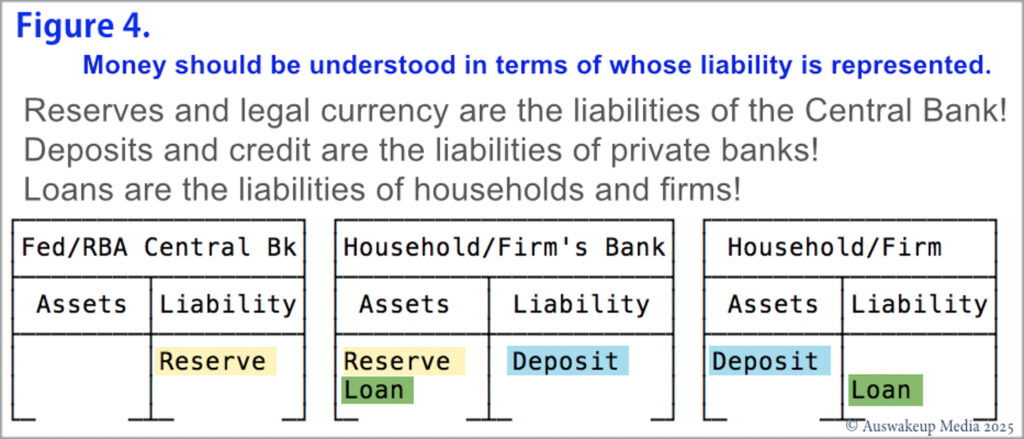

The title of Graeber’s book will be a focus for defining money for this article (Graeber, 2011). The concept of “debt” liability facilitates the differentiation between various forms of “money” from the outset. The inclination to ignore liability is central to misinterpreting the phrase “Taxpayers’ money.” Though legal currency (cash) is a subset of money, all currency and money, if properly described, need to be identified economically in relation to whose liability it is. This, however, is not the perspective of orthodox economists regarding money.

Orthodox economists generally tend to overlook the role of money in economics and typically refrain from incorporating it into accounting identities, such as “liabilities” and their attribution. Chartalists, who understand that barter was not the origin of currency systems, perceive money dominantly as a state creation designed to regulate and structure economic activity. Money, as a formalised record of debt, has historically taken many forms, from clay tablets, tally sticks, and royally minted coins. Though in a contemporary setting, it should be acknowledged as a broader liability of an entity or institution. The liability for legal “currency” rests with the State, as explicitly stated by the currency in any citizen’s wallet. In Australia, currency notes feature an inscription indicating their status as “Legal Tender,” issued by the “Reserve Bank”. In this context, all legal cash functions as a liability of the Central Bank, an instrument of law, issued by the government and backed by that Central Bank. The concept of “liability” should be the primary distinction between different types of “monies”.

Currency Creation.

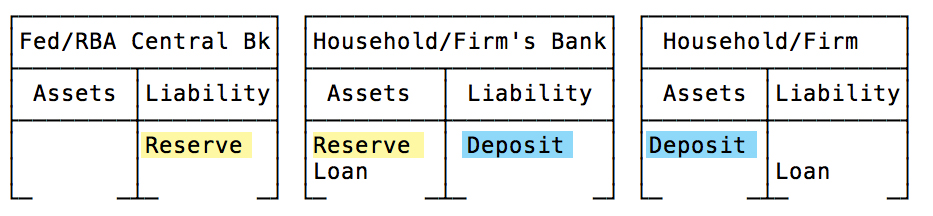

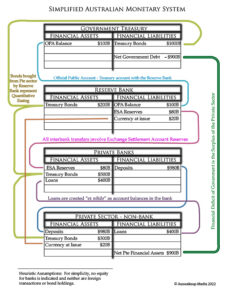

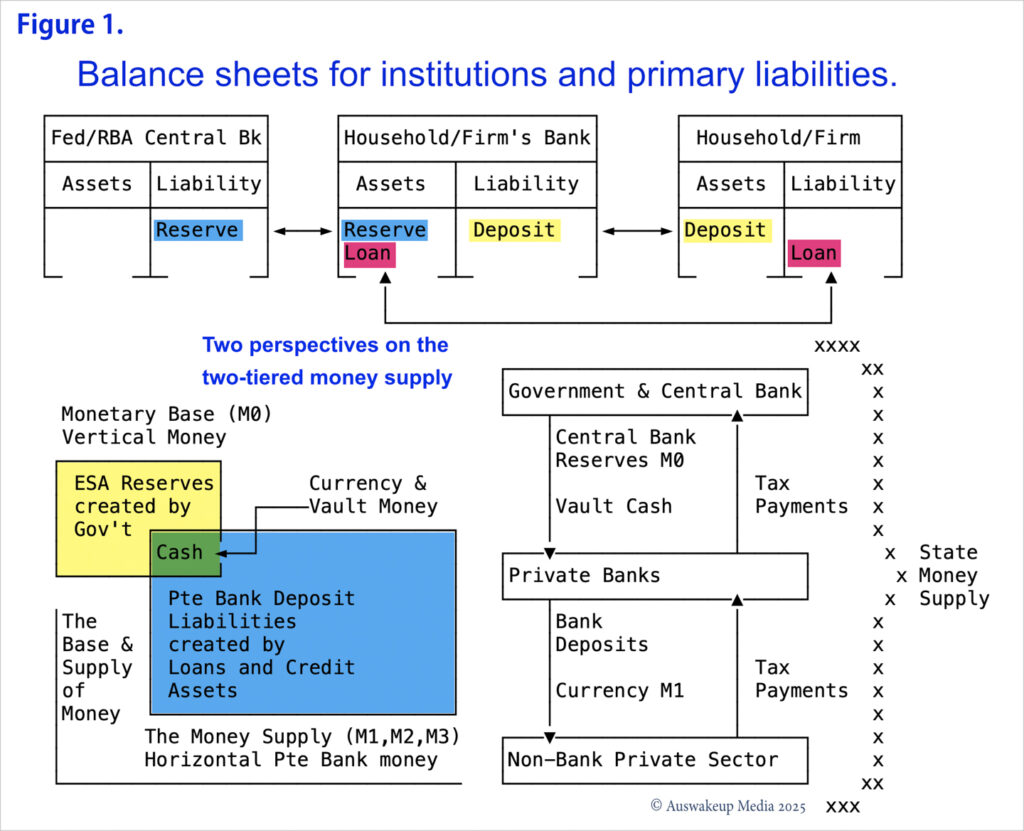

Only two legally specified entities are authorised to supply all legal currency and credit, whether tangible or digital — either the Central Bank or a private bank. The latter is granted legal authorisation to operate by the Central Bank and holds financial accounts with that singular bank. This article will preclude “Shadow Banking,” which operates independently of the central bank. These entities are the financial clients or subsidiaries of the private, licensed banking sector and do not hold accounts with the Central Bank.

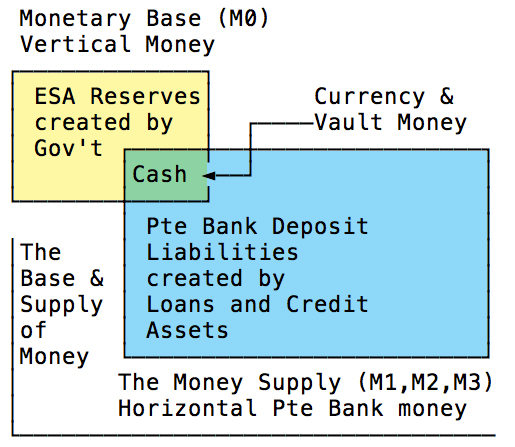

Central Banks issue currency, referred to as “reserves” — also commonly known as vertical money or M0 money — to the accounts of the private banking sector. “Reserves” are the Central Bank’s liability. This is distinct from private banks’ accounts, which are held by non-bank entities (such as individuals and firms). These entities maintain accounts circulating the money that operates in the non-bank economy, such as loans, deposits, cash and credit. This pool of financial assets is commonly known as either M1, M2 or M3 money. Henceforth, as a simplifying heuristic assumption, we will incorporate M2 and beyond under “M1” as the different measures of monetary liquidity are incidental to this discussion. The sole form of “money” that bridges these internally circulating two-tiered monetary systems is hard cash. Modern cash tends to approximate 3% of the “M1” money supply, depending on the economy. The Central Bank issues/prints cash in proportion to the amount that private banks deduct from their reserve accounts with the central bank.

Credit Creation ex nihilo.

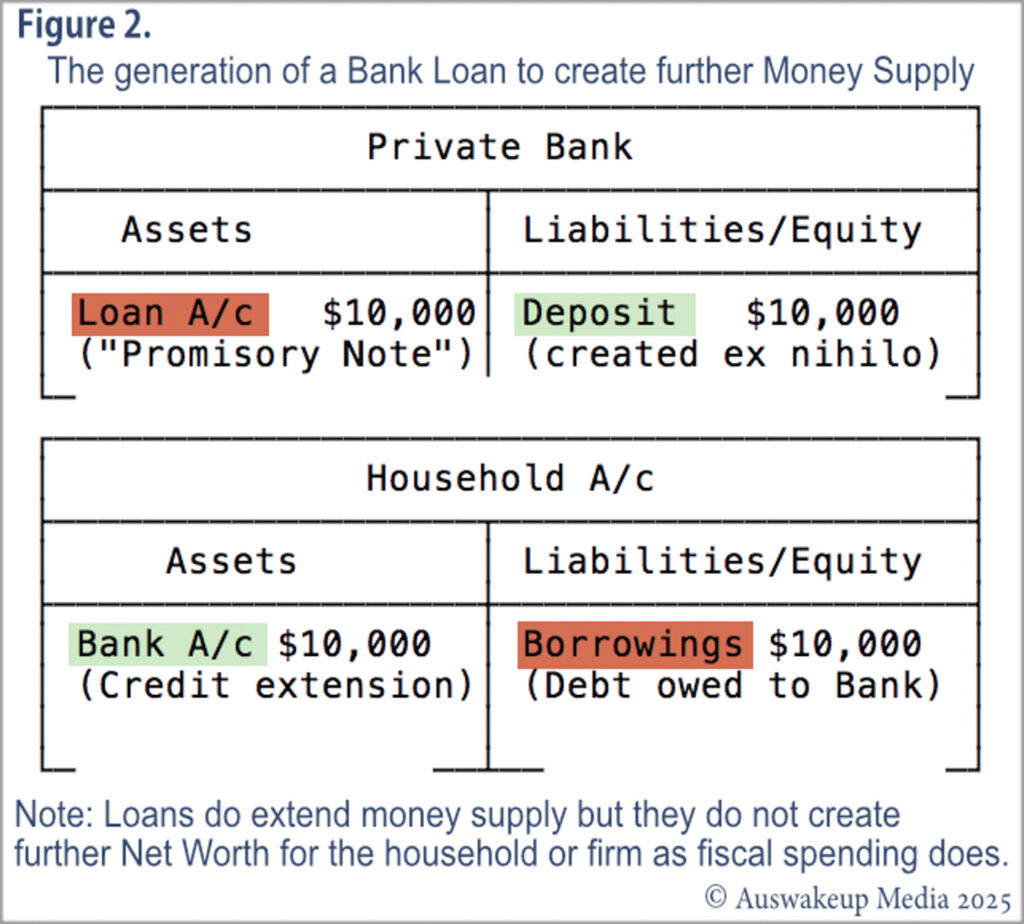

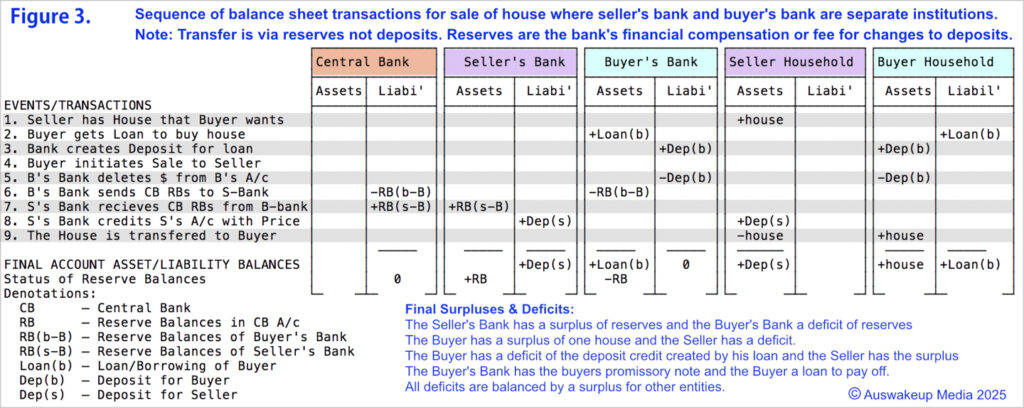

When firms or individuals seek a bank loan in a specific currency, the bank establishes a credit deposit liability. This is balanced as an accounting identity against a legal “promissory note” bank asset. The “promissory note” is the balancing bank asset that commits the borrower to repayment of the bank’s loan-deposit liability over time. The bank generates a credit extension, as a “deposit” liability. This entry on the borrower’s balance sheet indicates the acquisition of a new deposit asset, while the loan deposit is categorised as the borrower’s liability. These counter-balanced entries represent the complete balance books of the bank and borrowing entity pertaining to the establishment of a loan.

Contrary to popular opinion, previous deposits in bank accounts or reserves maintained by banks with the Central Bank do not play a role in the initial loan transaction. Neither exists as a source for a bank loan. These are among the more common misconceptions known as the “loanable funds theory” or “fractional Reserve banking”. Several other heterodox economists have debunked these apocryphal myths, which require no further discussion here (Hail, 2016).

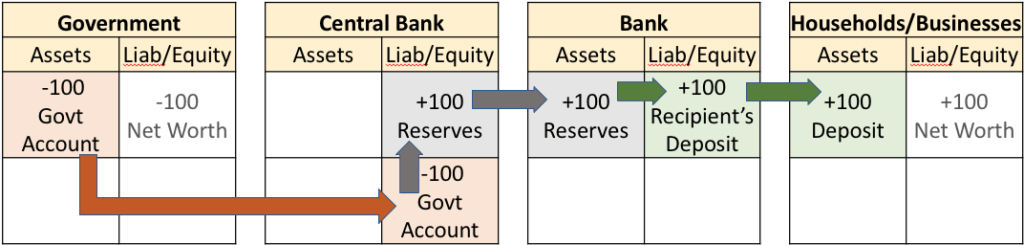

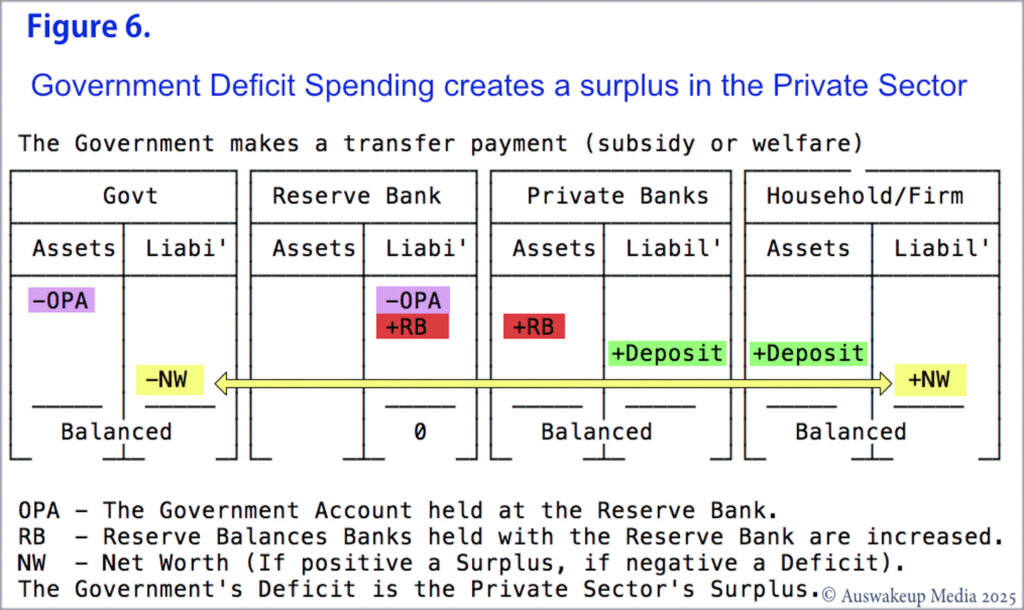

A licensed bank follows the identical accounting transaction procedure used for all other interbank transactions after the loan is established. Transferring credit deposits to another private bank uses Central Bank Reserves account assets. Despite individual account balances being credited or debited, banks exchange reserves, not deposits. Sending public entity accounts will incur a “deficit”, while receiving bank private accounts will gain from a “surplus”, as with any transaction. Similar to how a government deficit creates a private surplus. {see Figure 6}

Exchange Settlement Accounts with the Australian Central Bank hold the M0 reserves of private banks. Private banks hold loans, deposits, cash and credit (M1 money). Private banks’ vaults or your “wallets” contain cash issued by the Central Bank. These combined account deposits and personal cash holdings represent the entire economy’s monetary supply. Modern monetary systems are characterised by a hierarchical two-tier system that maintains the separation of M1 and M0 currencies.

My personal involvement in these processes was as a contract employee in both institutions. From August 2001 to October 2002, I was a contractor to the Reserve Bank’s technical team, responsible for insourcing the computer systems that handled the Exchange Settlement system. The Reserve Bank’s exchange settlement computer had previously been outsourced. Previously, from August 2000 to August 2001, I had worked on the financial computer systems for Westpac’s Private Banking System. Such a background informs this author’s knowledge of these institutions that circulate currency in the economy. In 2003, I was contracted to facilitate the outsourcing of one of Westpac’s finance systems to a firm called “Datacom”. Should the reader doubt my candour in this monetary description, then the Mcleay, Radia, & Thomas (2014) article by the Bank of England’s Central Bank will provide an identical stance.

Ultimate Liability for Currency.

All currency is issued by legal decree by either the State or its legal proxy, the banking system. None of this constitutes the currency of the taxpayers, whether it pertains to M0 or M1 money supply, regardless of self-possession. The key issue is who has liability. Currency is not your liability unless you are a Central Bank. Any entity can be liable for a debt, for which currency in one’s possession may be payable, but the currency itself is the liability of the State. That State does not recognise legal currency as the taxpayers’ ultimate liability, as the State’s counterfeit laws firmly safeguard the state-recognised legal currency. Private banks hold the authority to issue cash on behalf of the State; however, they are required to surrender their reserves to enable the Central Bank to issue hard cash, which also remains a liability of the Central Bank.

Taxpayers’ money.

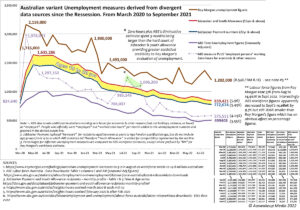

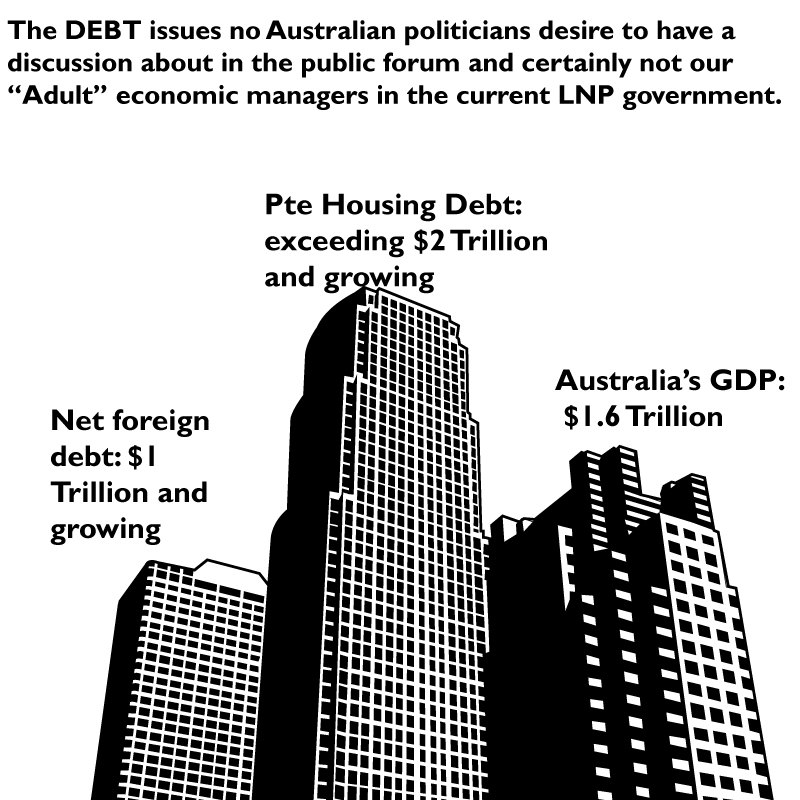

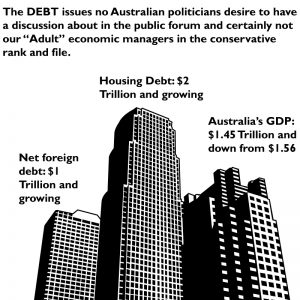

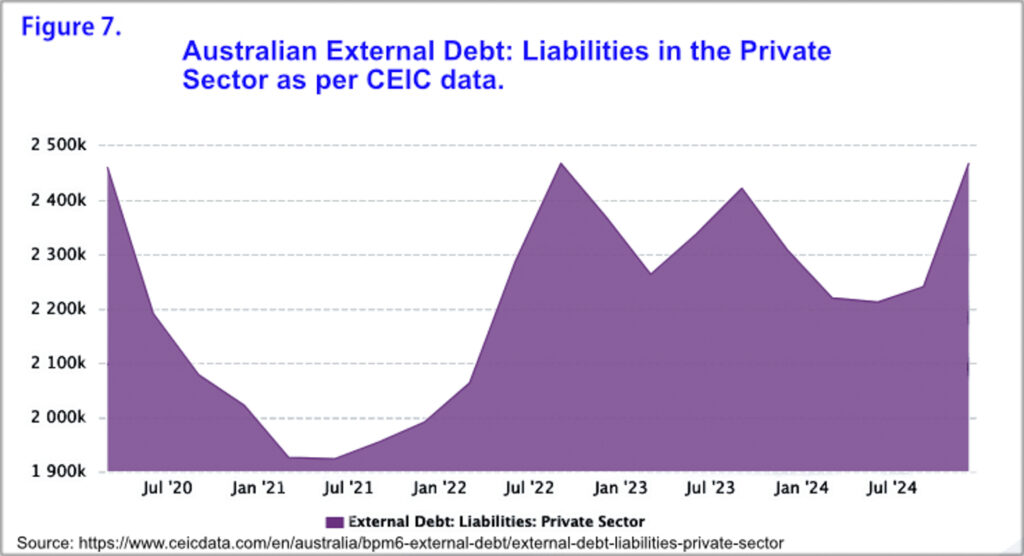

Australian taxpayers’ dominant liability is private bank loans, which had dropped sharply post-COVID due to government expenditure facilitating loan payoffs. After that, private debt rose again in recent years. CEIC Data reported 126.28% of nominal GDP in December 2024 (CEICdata, 2025). We will come back to that.

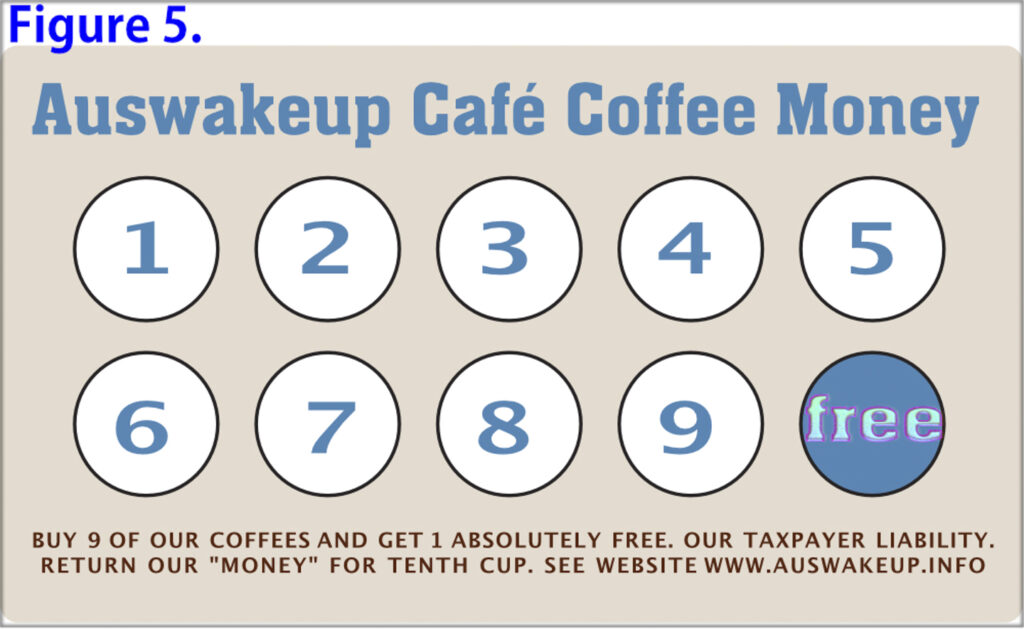

The other liability that constitutes “taxpayers’ money” is their issued “money”; however, it is not classified as “official currency.” This is a necessary distinction. Currency is not within their State-sanctioned authority to issue; however, it is essential to clarify that any taxpayer has the capacity to incur debt, hold a liability or create “money”. Individuals and organisations (who are also taxpayers) often create liabilities, which fundamentally represent “money”. In its simplest form, the coupon card obtained from a café for regular morning coffee, which offers the 10th beverage without the exchange of state-recognised currency, constitutes a form of “money” by definition. The café owner assumes accountability for the card, which, when presented with the inclusion of its nine stamps, is returned to the café owner as compensation for the tenth cup of coffee. This liability constitutes Taxpayers’ money.

The discount card that one might obtain from a supplier seeking to encourage patronage, is literally, taxpayers’ money. The company’s stock option, which is given to an employee and confers ownership rights without exchanging legal currency, is essentially taxpayers’ money. Multiple “monies” exist to replace state-recognised legal currency. Anyone can issue “money”; the problem is securing acceptance for that notification of your liability. In 2022, a small local community of artists in Castlemaine developed the “Silver Wattle” clay money project, which served as a form of local currency for exchange (Lawrence, 2022). These are the limits and scope of taxpayers’ money. These monetary generations have never included state-issued legal currency, unless the taxpayer was willing to risk 10 to 14 years in prison in Australia for counterfeiting.

Issued Money.

When the State issues currency, typically through fiscal spending, the Central Bank assumes the liability for this currency. If you are the issuer, the liability rests with you; however, it does not constitute a “debt” that necessitates repayment. Similar to points in a game, there is no technical limit to the number you can issue. While there are consequences associated with issuing an excessive number of points, one may choose – however unwisely – to disregard the consequences. While not always a prudent decision, it is essential to acknowledge that, regardless of the outcomes, the options are at least pragmatically boundless.

Issuance does not need repayment. Corporations receiving welfare to support business operations, or unemployed individuals obtaining subsidies, are not required to repay these funds to the issuing authority. (Yes, that characterisation of State payments was deliberate.) The coupon issued to you by the shop owner, in their capacity as a taxpayer, is not a debt owed by you. Their issue is their liability, not your debt. You do not owe the café the stamped card for your free coffee. They issue it to you, and you obtain their liability. Only loans require repayment.

Taxpayers can refuse to honour their issued money. They may change their local currency status, like Australia did in 1817 with the Bank of New South Wales issuing the Australian Pound and in 1966 with the Australian Dollar (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2021). British and Australian pounds are no longer accepted for taxes. Only State-issued currency is acceptable for tax payment. Australia uses the Australian Dollar! Moreover, you cannot pay your taxes with Taxpayers’ money, except where it is a private bank loan denominated in the State’s currency. Any other taxpayer liability is off limits for tax payments. Therein lies the reason for the initial acceptance of legal currency, as a Tax liability demanded by the Federal Government that national residents can only acquire by earning or borrowing it.

It is only truly a refundable “debt” if it is a loan. Money users are restricted by law from issuing “money” that is not their liability. They can exchange, utilise, or destroy issued money; however, in order to acquire the monetary liability of another individual, they must have it issued or loaned. If a bank provides credit as a loan liability on its accounts in exchange for the asset of your promissory note, you are obligated to repay the bank. If the State offers a subsidy, you have no legal obligation. One doesn’t expect the Umpire who issues scoring points to have you return them, once the game is over.

Issuance of a Surplus

If you have to return the “coffee card” to get the 10th free coffee, the issuance of “money” has value. Taxation has a similar intended purpose. If the issuer requires a taxed return that does not equal the total worth of the money issued, the issuer has a “deficit”. The amount in deficit is not a “debt”.

It is a deficit.

It is a difference!

It is issuance minus collection.

It is spending less taxes.

The emerging café economy.

If you spend $5 for coffee, you have a $5 deficit, and the café has a $5 surplus. The café owner accepts liability for a printed card that indicates, ‘after nine purchases, they will accept liability for the tenth coffee on return of your card.’ Returning that “money” is the equivalent of a “tax”. You can’t use it again, and hopefully, the café may issue you new “money” once it is spent. By accepting the “tax” of returning the card, you benefit from using the café’s money, which is why you value it as local money. As any café owner will pragmatically concede, not all cards issued are returned, and not all customers come back. Even Taxpayers’ money runs a deficit. Their customers hold a surplus, and perhaps they trade them if they are leaving the area. And so, springs forth the coffee card economy. The “taxed” taxpayers’ money/card, when returned, is usually trashed. The Taxpayer café owner issues new money if he wishes to continue issuing taxpayers’ money. The owner fiscally spends into his local community. The café community is thus represented as a microcosm of the issuance, trade, tax and destruction of money in an economy.

Deficits create Surpluses.

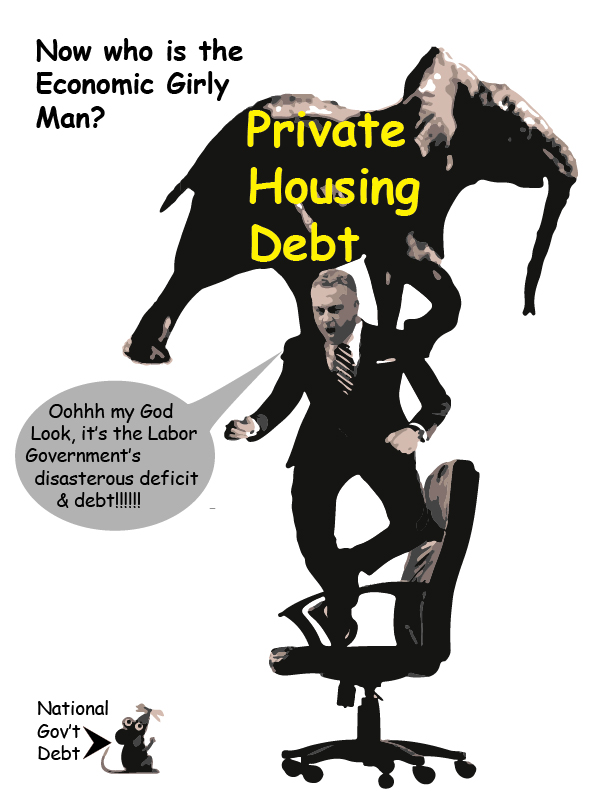

The issuing of money by the government generates a surplus for the private sector. What the government does not tax back remains the balance owned by the economy’s “customers”. When our Treasurer Jim Chalmers talks about a surplus in a particular year, that implies he taxed more than he issued, leaving the economy short-changed. Just like the café, you cannot tax back more than you have issued during the course of the café’s existence. Doing so would imply expecting your clients to return cards you have never issued. This would effectively bankrupt your local monetary system. If your café has been open for a long time, you can reclaim more cards than you issued in a given year, exhausting the card supply in your market from previous years. Similarly, when Chalmers delivered two consecutive public government surpluses, the monetary surplus in the private sector decreased. So, what does the private sector do when the money supply is low due to the Treasurer hoarding all of it? They take out loans (Chinnery, Maher, May, & Spiller, 2024). When John Howard and Jim Chalmers ran surpluses, what did the private sector do? Citizens’ debt to banks grew as they sought financial assistance (Tiffen & Gittins, 2009). Recall now the previous comment about CEIC Data?

Again, if the currency issuer gives $500 in welfare to a firm and taxes $50, the firm has a $450 surplus, and the issuer has a $450 deficit. Government deficit is private sector surplus. Alternatively, if the currency issuer taxes the firm $600, the firm is in deficit by $100, and the issuer is in surplus. It is just basic accounting or mathematics. The firm presumably does what? To survive, borrow $100 or more. A public surplus is typically detrimental to an economy. The only way in which that $600 tax does not cripple a firm, is if the business cycle has been good enough in past years to absorb the loss.

Summary

Taxpayers’ money is money that results in a liability for the taxpayer. Government currency is that which creates a liability for the government’s bank. Taxes to the government are “currency” returned to the currency issuer. Taxpayers’ taxes are the “money” that the taxpayer café owner receives from the returned coupon. Taxpayers’ money, except where it is a bank loan in the government’s currency, is not an acceptable form of payment to any government. When the gap between money issued and money taxed leads to a deficit for the issuer, the economy (local or national) is likely to be thriving. If the issuer is in surplus, the economy (local or national) is most likely in distress. The need to surrender a tax on the money supplied by the issuer provides initial value to the money and increases its likelihood of being accepted.

The issuer can always choose not to issue a monetary unit and instead provide a replacement unit with no debt attached to the previously issued. The café owner is liable for the “money” paid in coffees unless the café decides not to honour that card and replaces it. They may choose to replace any old cards with new ones at their own preferred exchange rate (i.e. it’s now the fifteenth round). Governments have done this throughout history. Argentina has done it four times. Australia has done it twice (although some will counter that there is a lack of fundamental distinction between a British and an Australian Pound). Issuing currency does not generate a “debt” to the recipient; instead, it creates a responsibility to honour that issuance (until it is no longer honoured). This changes as the law changes, because currency is a legal construct of the State. To use another analogy, if you offer points to the “game,” you cannot run out of points unless you, as the issuer, consciously decide to stop issuing points. That is what “Austerity” is!

Epilogue

Now, there is the unmentioned issuance of bonds that governments engage in to create a debt that they choose to “cover” the deficit, but that is a financial choice and, frankly, a discussion for another article.