“We are bringing the 457 visa class to an end”, announced Mr Turnbull after Easter, “…We will replace it with two new temporary skills visas.” With a quick sleight of hand, Turnbull re-branded the much criticised 457 visa with two – as yet unnamed – programs to bring foreign workers to Australia. Though new rules and security checks were mentioned, he ensured that he would guard us against the impending “threat of permanent citizenship” of intelligent and skilled foreigners whom our employers have sought out. Rest assured, Turnbull has proclaimed he will keep us safe from having people of this calibre, stay in Australia.

As Australia returned to work after the Easter long weekend, Malcolm Turnbull reminded us we were a nation of immigrants, but we should not be overrun by too much more. With the Australian workforce apparently foremost on his mind, Turnbull told the nation (first via Facebook) that the 457-visa program was being scrapped for two new innovative temporary foreign worker schemes to tackle our unemployment issues. In restricting that program and although unnamed, he proposed two new visa programs with fewer job role options, new market tests, English language, skills and experience requirements.

The first reminder that comes to the fore concerning these new reforms that “put Australian’s first”, is a reference to the similar policy I’ve previously heard. Didn’t Julia Gillard propose something similar herself in 2013? Didn’t Malcolm Turnbull criticise her for striking at the “heart of the skilled migration system”?

457 in decline?

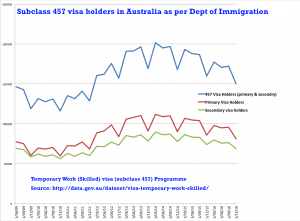

Leaving Turnbull’s change of perspective aside, the numbers of 457 workers in Australia have been a subject of much speculation and false rhetoric by politicians seeking to introduce alternative facts and in some cases, outright bigotry. 457 visa numbers have been following a pattern of decline in the last few years but a significant aspect of that in the annual cyclic pattern.

Regarding the 2016 decline of numbers in Australia in any quarter – providing you limit your scope – it looks significant. The first quarter of 2016 (March) there were about 177,390 people in the country working under 457 visas.

Since then it dropped slightly to 170,580 (June), up a little to 172,187 (Sept), and dropped significantly to 150,219 (Dec). Now, while these last figures may create the illusion of a significant fall, you need to look at the seasonal pattern of numbers over the last few years. Stepping back and reviewing the last seven years, a pattern emerges for every year. (Rising sharply, slight fall, slight rising, sharp decline) The pattern – as graphed here – will show you that it is about to jump back up again, so there is a deception inherent in quoting the last quarter’s figures of any year as indicative of where 457 numbers are or will be. 457 visa data have a predictable annual cyclical pattern. Turnbull’s timing made before the Department of Immigration released the last quarter’s figures creates the short-term illusion in media reporting that the coalition is indeed clamping down on 457 workers.

Workers come and go. Totals expressed in net movements of visa entrants – over periods such as a year – hide the significant seasonal change in numbers in the country. So when it is stated that 33,340 of the 40,100 primary applicants lodged 457 visa requests in the first quarter of 2016 were successful and that this is a decrease from the same time last year, what is notably absent is how many 457 workers left. This is also dependent on which quarter you choose. So pointing out that – during the third quarter of 2012 under Gillard – that 35,452 foreign workers entered the country, ignores that only 14,665 came in the last quarter of 2009. The coalition cherry picking numbers from specific quarters to disparage Rudd/Gillard’s record – that in actuality had both the highest and lowest intake of 457 Visa workers – is perhaps a tad disingenuous.

Annual cycle aside, it is still true to say the average number of 457 workers in the country since the coalition took power has been larger than the number of government recorded job vacancies in Australia. To keep it in context, the last 457 worker totals released by the Immigration department said there were 165.9K vacancies in Dec 2016. 457 workers had done their customary annual December quarter drop to 150K, down from 172K in the previous quarter. Unemployment at the time (Roy Morgan’s figures) was over seven times that amount at 1,186K or 9.2%. If you added Morgan’s December underemployment numbers to the unemployment, then you reach a number nearly 16 times the vacancy rate at 2,584K. I am not going to entertain the ABS figures because of their inherent inaccuracy.

So even if you threw out all the 457 visa holders in December representing less than 1% of the workforce and made all their jobs available, it would have little impact on the 2.5 million both under and unemployed. This is particularly the case, as the presumption is there are no available Australians in the market who have the skills necessary to fill these roles. This begs two questions.

- Why is it so?

- Is it so?

Why 457?

Introduced by John Howard in 1996, the 457 Visa program has been beset by concerns about fraud, corruption and need. Fraud, we will get back to, but the need for it is still a failure of policy. Howard claimed it was to enable employers to address labour shortages in the Australian market and yet after 20 years; we still need to address skill shortages? You’d have to wonder after 20 years, about an economy and a national policy framework that has so failed to raise the skill levels in Australians, that we still need 457 visa workers. How is that “in the national interest” as Mr Turnbull so frequently repeated? A medical degree takes 6yrs, engineering 5yrs and a commerce degree 3yrs. So what has the government been doing for the last two decades? Why have we been unable to educate and upskill our population? Why is this foreign labour market even necessary? To answer that, we need to go back initially to Howard and ask how he began to prepare our children.

As a western nation which once boasted of free education for its population, the growing restriction of education to the people has had consequences for our labour market. Howard changed how education was funded by allocating considerable funding to private schools and undercutting public schools. Students drifted away from public schools to the better-funded private schools, where they could afford the luxury. The public education system retained a community of poorer demographics with less time or capacity for higher education and an increasing inequality of educational results. The social class division between the affluent and the underprivileged then began at school for children. Two decades later the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey shows Australian children falling behind in education. Segregated our schooling system by either academic or social class boundary have been largely to blame for our children’s poor performance. Our ranking for investment on the OECD league tables for education is 22 out of 37 1n the OECD. Small expenditure is followed by weak results.

Whitlam onwards.

Leaving high school for TAFE or University has done little to revoke the class distinctions established by Howard’s redistribution of education funding. Whitlam abolished fees for TAFE and university students and provided support for apprenticeships through the National Apprenticeship Assistance Scheme (NAAS). Hawke reduced funding and re-established costs to students as well as changing labour market programs around apprenticeships and introduced traineeships as a significant response to rising youth unemployment. Trade apprenticeships flourished as the government focused on traineeships. Mr Keating started governments down the neo-liberal path of privatising the public sector. The problem with privatising the public sector was that these were the main generators of apprenticeship training such as electricity utilities, telecommunications, defence industries, rail, roads, and Australian airlines. Howard also continued to undermine the public sector which contributed to a reduction in skills training – via public sector apprenticeships. Howard quickly consolidated apprenticeships and traineeships under a single umbrella and wrested it away to unions and into the hands of employers. Skewing support for apprenticeships profoundly in the interests of employers was followed by a decline in training delivery, apprenticeship completions, pay and conditions. None of which was aided by the further dismantling of the industrial relations system, through the introduction of enterprise bargaining. While Rudd and Gillard dismantled Howard’s “work choices”, they still followed the traditions of the Hawke/Keating legacy by “make[ing] concessions to the big mining companies, reduc[ing] corporate tax, and restrict[ing] unions rights and push[ing] through spending cuts to maintain a budget surplus.” The decimation of manufacturing under Abbott destroyed yet another training base for trades and reduced the intake of apprentices. The budget cuts of his administration also severely impacted apprenticeships. Tracking the causes, consequences and level of damage to our employment economy have been made all the more complicated by Abbott’s savage dismantling of expert advisory panels as compiled by Sally McManus.

The combination of factors including the dismantling of education, expert advice, the industrial relations system and the public sector meant that a four-year apprenticeship in the building trade gets replaced by a shallow sixteen week CBT course as the bare minimum for that particular role. The results were described as “a disaggregation of skill which is ‘modularised’, ‘flexible’ and ‘atomised’ … [that] will ultimately leave skills ‘fragmented’ at their core.”

Many apprenticeships as a means of training up in skills for increasing levels of youth unemployment have mostly vanished by comparison. For example, Federal funding for NSW Tafe reached it’s zenith in 2011 and after that decreased. Deregulation of training provision meant funding to non-TAFE, and private providers increased by 20%. The consequence of this produced the rise of dodgy private providers of vocational education and also the unscrupulous practices by some private providers which have become a scandal in Australia.

Add too, what Abbott euphemistically referred to as “Fee Deregulation”. Attempts to rectify the class based education system via Gonski funding were scrapped, and the vocational training sector simply received new student loan systems, all of which has done little to encourage Australians to “buy” education. The result has been a drop-off in the teaching in Australia as students fall by the wayside, get ripped off or – even if they do complete their degrees – are faced with indexed debts that limit their employment capacities. All this in a market of decreasing full-time jobs, low vacancies and huge competition from other under and unemployed members of the workforce. Skills shortages have been a function of deteriorating access to Education driven by political policy.

Is there a skills shortage?

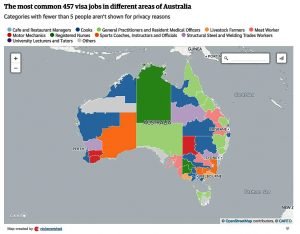

It is, of course, true to say we do have skill shortages. The question as to what extent any occupation is genuinely suffering from a talent shortage – is problematic. Questions arise as to whether the request for that skill just represents an opportunity for an employer to take advantage of a compliant, cheap and de-unionised workforce. Most reports whether from Flinders University or the National Institute of Labour studies have all rather reflected the opinion of the Flinders University report that “Despite the attention paid to skill shortages, the evidence used to evaluate their incidence and the causes and responses by firms remains thin.”

The problem predominately is that the labour market testing for skills shortages will still be conducted by employers – not by an independent panel. Employer “testing” will do nothing to affect the corruption at the core of exploitation of 457 workers.

Turnbull has announced that 216 job roles that are not covered by the renamed 457 visa scheme. The problem is that Turnbull’s new visa jobs list would affect just 9 per cent of the current 457 visa holders. So mostly he has cut an already redundant list of skills requirements – at least a quarter of which have had no application for in the last year. Turnbull has not addressed the issue of employer rorts because the determination of a genuine skills shortage has been so easy to defraud. Underpaying 457 workers has been pervasive amongst dishonest businesses.

In the absence of a plan to rectify education, the public sector, independent labour market analysis, unemployment, jobs and growth Malcolm Turnbull’s reinvention of the 457 visa scheme does little to aid Australia out of the economic malaise. Without attention to this issue now, we’ll be obsessing over skill shortages and “temporary” foreign workers in another twenty years.