Voting is the expression of the rights of an individual to participate in their government, but like any expression, it can be misdirected, coerced, bought and sold. Political Parties understand the role and importance of marketing, propaganda and salesmanship in seeking your vote, irrespective of whether it is in your or your community’s best interest, or aligns with your values.

Value development.

For the rest of us, our political attitudes are not always based on careful consideration of policy. Instead, a range of factors including gender, family, religion, race and ethnicity, and early childhood environments are strong predictors of political beliefs.

However, we arrive at our political beliefs; the next question we need to ask is, who in the political spectrum best represents those beliefs. This may be discovered by:

- an analysis of the policies and their consequences

- an evaluation of the perceived integrity of the political party

There is a range of political analysis strategies to make a systematic evaluation. Though this does presume that:

- Any of us spend any time to analyse the policies of political parties.

- Politicians can be trusted to follow through on their promises and ideological pronouncements.

- Politicians represent their constituents and not the interests of well-financed lobbyists and donors.

Instead of a rationally researched choice, research demonstrates that we engage in:

- Bandwagon voting [1] in which people’s voting preferences are reflecting a desire to follow trends and “hop on the bandwagon” regardless of the underlying evidence. [2]

- Reluctance to change voting patterns as other research from Europe demonstrates that voters do not adjust their perceptions according to what parties advocate in their campaigns. [3]

- A lack of comprehension of essential differences between the major parties motivated by the desire to decrease the potential costs of post-decision regrets. [4]

Major political parties actively encourage bandwagon voting. A prime example is an argument that you should vote for a major party on the pretext that that is more likely to win, instead of voting for the minor party which holds policies with which you agree. This argument ensures you throw away your real choices, for a compromise with values you don’t own, for people you would rather not have in power and relinquish your one element of control to power brokers. I can only assume this must be very empowering for someone, just not the voter.

The reluctance to change your voting patterns despite disagreeing with what parties advocate is a common problem in every democracy. Pensioners expressing anger at being shafted by the government, then declaring their continuance to vote for the same party, may seem odd to an outsider, but we know it happens.

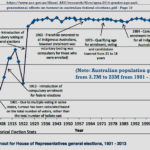

Failure to comprehend essential policy differences underpins the high incidence of informal voting in Australia of around 6%. The percentages of voter turnout failures and eligible voters not registering has also increased over time, although offset recently by the Marriage Equality plebiscite voter enrolments. Informal vote margins could have changed outcomes in electorates and possibly even the election of 2016. Many are content to throw away their only leverage in politics; protesting that we don’t like our options when we don’t know what our options are. These folk are highly disengaged with the ability to change politics but are very deliberate in expressing their political disappointment.

Left or Right

Other issues are the misperception of where your values lie on the spectrum between left and right wing, or “progressive” versus “tyrannical”. Some other people are sufficiently misled in concepts of political theory to associate socialism with the Nazis or can’t distinguish between communism, socialism, capitalism and democratic socialism.

To aid objective rationality researchers examine party policies, attempting to map a parties position on the political spectrum. The ABC’s vote compass tries to help voters understand their position relative to each of the main political parties. The ABC describes its online survey as a civic engagement application, where one can:

“Based on a user’s responses to a series of propositions that reflect salient aspects of the campaign discourse, Vote Compass calculates the alignment between the user’s personal views and the positions of the political parties.”

Its critics suggest it’s an insular Australia-centric representation of political ideology, treating the Labor Party as Left-wing party and the Liberals as Right-wing party. The Greens and One Nations are treated as political extremists. The basis of the perception is that it reflects community attitudes. There is an apparent political reluctance for the ABC – and the “political scientists” who designed the “compass”, – to challenge the status quo or adopt an international perspective.

Democratic Socialism or Nationalist conservatism.

The Liberal Party in Australia sees themselves as conservative which former prime minister John Howard described as a “broad church”. The Labor party still see themselves as a left-wing “democratic socialist party”. Oddly both Labor and Liberal suffer from the delusion that they are progressive parties who are at odds with each other when they are really merely in heated agreement. Some pundits legitimately note there are left and right factions within both Parties, but the party as a whole, cannot be both. Both Labor and Liberal party candidates vote as a whole and discourage “crossing the floor“.

The party as defined by what its policies support, must by logical necessity, establish itself as either one or the other, independent of its internal divisions. As such, I am not interested in the individuals but the gestalt organisation. Also, I want to introduce a more global view of politics rather than the insular ABC Vote compass. A broader international perspective lifts us away from the tedious bias criticisms levelled at the ABC from both “sides” of the political spectrum.

How the world sees the political spectrum has changed since it was simplistically regarded as American capitalism versus the communist Soviet Union. This died with the Soviet Union’s restructure via Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost and perestroika. In the latter part of the 1980s, as the walls came down in Berlin, perspectives changed. The attitudes of Menzies’ worship in the 1980s that framed perspectives for political engagement, for men like Tony Abbott, Joe Hockey, and Christopher Pine at college, have shifted significantly.

The Global Compass.

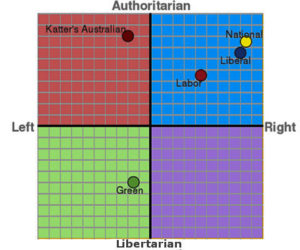

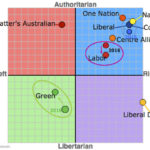

The internet phenomenon of the political compass did not originate from the ABC but from further afield from an older body of political analysts, who review politics from an international perspective as opposed to our myopic national perception. “The Political Compass” has been analysing OECD democracies since 2001. Their perspective on the political positioning of Australian politics is very different and revealing. The political compass provides a much more accurate assessment of the exact nature of the political positioning of parties in the Australian democracy (and for that matter several other democracies such as the UK, Canada, America, Germany, New Zealand, Irish, and European Governments).

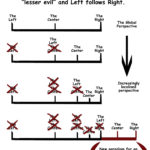

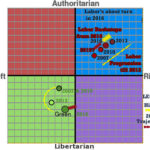

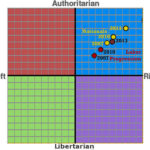

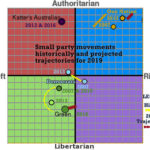

What is of particular interest to myself was to review their separately graphed analysis of each year to gain a perspective on how we have changed over time. To this end, I have overlaid the graphs from the last four elections as depicted by the analysis from https://www.politicalcompass.org/aus2007 to https://www.politicalcompass.org/aus2016. This show’s Labor as a right-wing authoritarian party that had been steadily marching further rightwards and more authoritarian until 2016 when it seems they took a back step.

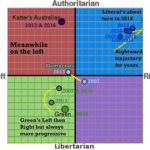

It has primarily followed behind the Liberal party, which, although always further right in political ideology at any instance in time, shifted towards the centre in 2016. While this shift helped the Liberals under Turnbull win the 2016 election, the Right-wing factions of the Liberal Party subsequently reasserted themselves. After a challenge by former immigration ministers Peter Dutton and Scott Morrison, the conservative Morrison claimed the Leadership of the party. The direction of the party reassumed the previous course to the Right.

Interestingly, the only party that has made no backstep at all was the National Party. They have stopped for nobody including their partners in the Liberal Party. If you are a right-wing voter who expresses some concern that the Liberal party has softened, then the Nationals have compromised for nobody. Neither, for that matter, has Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party.

Menzies & Whitlam

From 1949 to 1966 Sir Robert Menzies dominated conservative politics as the Prime Minister. While described by contemporaries as the Father of the modern conservative movement he was far more pro-refugee, pro-family, pro-freedom, pro-middle-class as the “The Forgotten People” broadcasts showed, then the current manifestation of the Liberal Party. Despite his support for the racist White Australia policy (which is an attitude that has run consistently through his party for generations) his later dismantling the policy and ratification of the UN Refugee Convention was far more progressive than what is exhibited by his party today with their indefinite detention programs. The conservatives held power until 1972 when Australia reacted to a long run of conservative political leadership and voted Whitlam and his agenda into power. By 1973 Whitlam’s Government changed immigration laws to repudiate race as an issue. Gough Whitlam from 1972 to 1975 shifted the political face of the country sharply to the left-wing. From the perspective of where Australia had been, his policies seemed radical. Some suggest that in comparison with the world stage, Gough was predominately only playing catch-up with many more progressive countries that had already gone down the path Gough was following. He admitted this in his 1969 election policy speech in Sydney Town Hall about education. Though to many Australians, especially the Right-wing, it was radical politics. While “The Political Compass” has taken no stock or measure of what the Labor Party looked like then, I suspect given the history of the movement of the Labor party in the socioeconomic, political spectrum, and it would be fair to suggest it was legitimately a Left-wing party at that time. It has marched steadily rightwards in the decades that followed.

Strange bedfellows

The only significant left-wing parties in existence anymore according to “The Political Compass”, were the Democrats, Bob Katter’s party and the Greens. Sadly, Don Chip’s political ambitions to “keep the bastards honest”, has been mostly lost to history. Bob Katter – while initially a member of the National Party – formed his party in 2011 and remained as a member of Parliament – neither gaining or losing ground. The Greens party, on the other hand, shifted towards the centre where the Democrats once trod, even taking on board as members, former state party politicians from the Democrats.

So regarding the left/right divides of the political spectrum, it is incorrect to think of it as between the ALP and the LNP. The real gap between left and right policies, ideologies, and social causes are primarily between the Greens on the left and the Labor/National/Liberal “coalition” on the right. Not of course, that the Liberals or Labor party would consider themselves in such an alliance, given their antipathy. In 2013 the political compass placed the Labor Party’s positioning under Kevin Rudd, to the right of the National party’s position in 2007 under Mark Vaile. Perhaps discovering the Labor party held a political policy position further to the right and closer toward authoritarian than the Liberal party’s partners (The Nationals) during the Howard years is undoubtedly challenging to some. While the conception of a Liberal/Labor coalition is unpalatable to both parties, keep in mind the Nationals under the Leadership of Barnaby Joyce had marched onwards unrelentingly rightwards and authoritarian and are no longer trailing behind the Liberal party the way Labor has done.

How far Right?

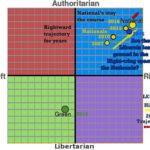

We should evaluate parties regarding their real and current political persuasions in the 21st-century rather than what they were in the 20th century under Menzies or Whitlam. The Labor “left” is no longer close to left-wing! If the rise of far-right nationalist movements from National Action in the 1980s, to Australia First, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation, Rise Up Australia (RUA), and the Australian Protectionist Party (APP), are any indicators, the two major parties are far more closely aligned. The political compass only charted One Nation in 2007 and 2013, but it is evident where on the spectrum it sits. In the absence of a re-evaluation for 2019, we must look to policy changes in parties to determine how far to the right-wing sit Liberal, Nationals, One Nation and Labor. Given the bipartisan agreement around legislation and policies over initial Adani Coal mining support (although there are signs of change recently), refugee detention, Foreign interference, Encryption laws, journalists and whistle-blower repression, Social media laws restraints, Low targets for NEG energy , website blocking, the PM’s war powers, cutting migrant welfare, Aged care funding cuts, costly education, private healthcare, Metadata retention, globalisation of trade, mandatory sentencing agendas, static Newstart allowances, criminalisation of abuse reporting and privatisation of public assets, it is not hard to deduce the policy direction. While they have differences on minimum wage (only recently), marriage equality, climate change, Medicare, tax cuts, Federal ICAC, negative gearing and infrastructure & economy, remember that the Labor party has voted with the Liberals for at least 40% of all Liberal legislative agendas since 2013.

How Far Left?

The only representative left-wing parties noted by the “The Political Compass”, were the Democrats, Bob Katter’s party and the Greens. The Democrats being the only real centrists to speak of had largely exited the realm of political influence but have returned to contest 2019’s election. The Green’s have floated around on the left side of the political spectrum becoming more Libertarian/Progressive over time but lately shifting rightwards. The Greens have been disparagingly referred to as “neoliberals on bikes”, but while it is true, they have as a party moved rightwards they are by the Political Compass’s assessment a long way from the Labor/Liberal/National neoliberal agendas. The Democrats and Greens are the closest to centrist parties Australia has.

Beyond these parties, the “Political Compass” has not assessed other left-wing or progressive smaller parties. These would include the Pirate Party, the Arts Party, Science Party, Socialist Alliance, and Reason Party, amongst others. The rise of small parties has been marked, and while the Political Compass does not evaluate them, recent emergents have been summarised in the embedded link here.

Choices.

As 2019 election draws close, whatever values you seek in a party, left or right, socially conservative or progressive, it behoves you to consider which party aligns to your values. So perhaps it is time to reassess both your perception of where your party of choice stands in relation to what you believe. As such “The Political Compass” test, may be revelatory.

In doing so, perhaps you might adapt the fixed impression you’ve held over the past, for where the party you’ve always voted for, has moved to in the dynamic and ever-shifting landscape of Australian politics.

If you are a member of any number of right-wing nationalist parties such as “Rise Up”, “Australia First”, “Love Australia or Leave”, then your mainstream preferences would likely be extended to One Nation, the Nationals and the Liberal party in that order. If that is too far right-wing for your liking, but you are still conservative, then the Liberal Party followed by Labor makes a good choice. If you are what many refer to as a conservative “small l” liberal or a mild to a moderate right-wing constituent, then the Labor Party is the only option left to the right. Should in that process, you discover your leanings are significant enough to the left of the Labor/National/Liberal/One Nation right-wing power block, then you have three main options in Bob Katter, the Democrats and the Greens and numerous small progressive party options to choose from, depending on if they have representatives in your electorate.

To many realising that “Labor” is a right-wing party and “The Greens” are the only progressive centrist mainstream party is disturbing enough to one’s decision process, without having to evaluate the real position of smaller parties. The public’s expectations of democracy in Australia are damaged enough already.

What’s in it for ……?

While there is inevitably, the hedonistic approach to politics, on which so many politicians count. All to garner your vote, with “What’s in it for me?”, as opposed to “What’s in it for my country?”! Might I remind you of the words of Gough Whitlam when writing in the London Daily Telegraph in October of 1989?

“The punters know that the horse named Morality rarely gets past the post, whereas the nag named Self-interest always runs a good race.”

—–//—–

Postscript.

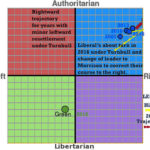

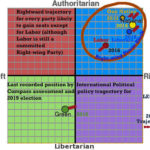

It is early Jun 2019, and the dust has settled on the election results, and the political compass has scored the positions of the parties, and I have an opportunity to assess the predictions made in the article above. The only significant miscalculation was with the Greens that appear to have moved leftwards but less progressive where – because of the rise of bipartisan agreements between the Greens and the Liberals changing from 8% under Abbott to 28% under Turnbull – that they appeared to be shifting rightwards. I conjecture that the constant references to the Greens being “neo-liberals on bikes” was responsible for a predisposition on my part to make inaccurate forecasts.

One Nation’s assessment was based on only two statistical variations (2007 & 2013), and it appears they haven’t shifted from their position from 2013.

In regards to all other parties, Labor, Liberal and Nationals, they have moved in accordance with expectations although the shift was more vertical along the Authoritarian/Libertarian axis. The Liberals moved approximately into the position the National held in 2016.

Except for the Greens, the political landscape was reasonably predictable, and it is still true to say the closest main party to centrist in the Australian political Landscape from a global political perspective are the Greens.

Footnotes:

[1] Rebecca B. Morton, Daniel Muller, Lionel Page, Benno Torgler (2015) “Exit polls, turnout, and bandwagon voting: Evidence from a natural experiment”, European Economic Review, Volume 77, July 2015, Pages 65-81, Elsevier [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014292115000483]

[2] David J. Lanoue and Shaun Bowler (1988), “Picking the Winners: Perceptions of Party Viability and Their Impact on Voting Behavior”, Social Science Quarterly Vol. 79, No. 2 (June 1998), pp. 361-377, [https://www.jstor.org/stable/42863794]

[3] Fernandez-Vazquez, P., & Somer-Topcu, Z. (2017). The Informational Role of Party Leader Changes on Voter Perceptions of Party Positions. British Journal of Political Science, 1-20. [https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000047]

[4] Craig Goodman, Gregg R. Murray (2007), “Do You See What I See? Perceptions of Party Differences and Voting Behavior”, American Politics Research, Volume: 35 issue: 6, page(s): 905-931 [https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X07303755]