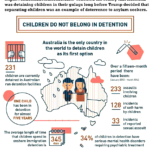

Deterring and imprisoning asylum seekers is gaining popularity in the western world. Punishment by separation of children from parents now has occurred in both Australia and America invoking community backlash. Many are unaware such practices have a long history in both countries. America forthwith will follow Australia’s indefinite detention practices, even as Trump repudiates his policy on separation of children from parents. These practices contravene the Refugee Convention to which both America and Australia were signatories. Dutton’s commentary emphasised the desire to be rid of this troublesome convention. He commented, “I think there is a need for like-minded countries to look at whether a convention designed decades ago is relevant today”.

I want to examine the relevance of international principles that underpin our history of refugee conventions versus “deterrence” against refugees and their smugglers. As I write this, it is Refugee week, so it is an ideal time to investigate the principles behind “deterrence”.

Human Rights convention

On the 10th of December 2018, Democratic Nations worldwide will celebrate the 69th anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human rights. Australia’s longest serving Prime Minister, Robert Menzies (a man no one will mistake for a soft-hearted humanitarian) signed the UN Refugee Convention on January the 22nd, 1954. Prime ministers that followed him, both Tony Abbott and John Howard spoke of him being the father of modern Australian Liberal ideology. The former Liberal Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser would have argued that in the 21st century, the Liberal “apple” has rolled a long way from that “tree”.

As we recall Human Rights Day, we will have long distinguished ourselves as the least compliant signatory to the Human Rights convention amongst any western democracy. When even North Korea can legitimately accuse us of human rights abuses, you know we have moved to the “dark side of the Force.”

Internationally speaking, things have taken a turn for the worse since World War II. We have now reached a point where both America and Australia are actively abusing people, including children, who have fled from torture and prospective death in their own country. Some have even died within our offshore gulags and deaths have already featured in Trump’s “zero-tolerance” regime. I want first to outline some historical legal cases which illustrate how international courts have responded to the idea of subordinating human rights to achieve political ends.

The German Autumn

Following the days from 1970 to 1977 clashes between the Red Army Faction (RAF) with Germany culminated in the “German Autumn,” and the kidnapping and murder of industrialist Hanns Martin Schleyer. Brett Walker delivered a speech to the annual Dinner of the Civil Liberties Society on Friday the 24th of November 2017 in Sydney in which he described the events of the German Autumn. The Germans had resisted the kidnapper’s demands. Schleyer’s son after failing to pay the ransom privately in part due to both inadvertent publicity and the German government’s reluctance then sued the Government in an attempt to save his father. The principle invoked was the invariable nature of human dignity by which he called on the government to make an effort to save his father’s life. The specific implication was that nobody should use another, as an instrument or means, to achieve an end. This included hostage-taking with demands. The court rejected the son’s claim in less than a day, and within days, his father was killed. Standing up to hostage takers has consequences.

Aviation hostages

In 2006, the constitutional court in Karlsruhe received a complaint from flight crew staff about the decision that the government had justification in shooting down aircraft held hostage in the air under the ironically named “Aviation Security Act”. The Bundesverfassungsgericht declared that legislation which would have allowed the German Air Force to shoot down hijacked passenger planes was unconstitutional and as a counterproposal reinforced the constitutional right to life and human dignity.

In reviewing the decision, the court would not accept the argument by the government that the passengers were very probably soon to die anyhow. They instead held to another principle, that the State could not reduce passengers and crew to the status of “objects” they can kill at the pleasure of the State, no matter the amount of time the people, may or may not, have left to live. The court essentially held that human life should not be used as a bargaining chip or as instruments to achieve an end of preventing the possibility of further deaths. Presuming that one would then be as guilty of the Machiavellian principle that the “ends justify the means“, which is, of itself, the ploy of hostage taking.

Machiavelli versus the Golden Rule

The categorical imperative in a civilised society is that we should act in a manner towards others that we think can, and should be, applied universally. Brett Walker espoused the principle that one should “do as you would have, you and everybody else, done by.” To extend this principle, it would mean that one would never abuse fellow inhabitants of this planet as instruments for some political end or project. The welfare and dignity of people is an end, but never a means by which you should cause one person or group to suffer to produce some advantage for others.

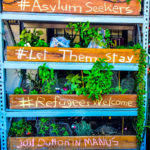

Instead, an alternate approach has been pursued with vigour and enthusiasm by recent immigration ministers such as Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton. Successive Australian governments (supported by the electors who have repeatedly voted for them) have created policies, legislation, and facilities, which are deliberately designed to mistreat and hold refugees and asylum seekers in conditions that we would not subject criminals in our internal national incarceration system. All designed and executed for the declared purpose of “deterrence.”

Under criminal law, the idea of “deterrence” is to sentence a legally convicted person, in a such a way as to deter others from committing such crime. It serves idealistically to deter the convicted person from re-offending. What is not part of the principle, is the notion of taking people who are not guilty of a crime and have not been convicted of having acted criminally, and visit upon them adversity and punishments to deter and modify other people’s conduct. That is abuse to use innocents as a means and abrogate their human dignity as an end.

Other democracies handle refugees far more efficiently and with less abuse than we do. But this perversion of law, criminality, morality and deterrence did not merely begin here with the likes of Howard, Ruddock, Morrison and Dutton! In fact, they have refined the “art” of this deliberate moral bankruptcy to heights which previously only totalitarian dictatorships or regimes have practised. Our pathway to abuse instead began with far humbler utterances from the lips of Labor politicians.

Queue jumping

While Keating is often attributed with the “queue jumping” rhetoric, the source of this phrase came from Immigration minister, Michael MacKellar, in 1977 in a Radio Australia broadcast. While Malcolm Fraser was attempting to placate the fears that hordes of Vietnamese “boat people” were descending on Australia, the Labor Party was busily trying to capitalise on fears about this “unchecked invasion”. Herein lies the original authorship of the fear mongering, which was eventually to become the backbone of refugee policy in Australia. Back then, the Australian public’s reaction, though cautious, was a far cry from the response of this century.

Bob Hawke and Paul Keating continued Labor’s negative attitudes towards refugees when they decided to use mandatory detention for asylum seekers at Port Headland, WA. This deterrent detention was the next step in both perspective and action. That act being detention of Cambodian refugees who arrived at Pedder Bay in November of 1989. They were held till 1992 while the government tried in vain to exclude these asylum seekers from seeking justice and the rule of law in the courts.

Like most immigrants, once allowed in and embraced, they became highly productive members of the Australian community. Up until that time, the maximum period of detention allowed for refugees had been 273 days. That limit in the Migration act was removed in 1994, paving the way for the era of indefinite mandatory detention. Similarly Trump’s executive order on June 20th – presumed to be reuniting families – seeks indefinite detention of families as a challenge a 1997 law that limited immigration detention to 20 days. (See Flores v. Reno).

Racism as policy

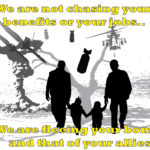

The success of Pauline Hanson’s racism in 1996 and the rhetoric of Phillip Ruddock in treating refugees not just as “queue jumpers”, but as cunning manipulators of peoples sympathy with an evil intention; marked a change in Australian attitudes. [Pg 31] The implication is that refugees sought to reap the rewards of an Australian Economy, steal our jobs out from underneath Australians, and then use their consequential “enormous wages” to finance terrorist plots against our nation. Not only does Australia’s falling wage rates make this unlikely, but the patient absurdity of the argument that traumatised people fleeing for their lives – often with their children – were even capable of such manipulation, was surprisingly and naively accepted by the public.

The proposition that terrorists hide out in detention centres was absurd back then and still is. Myths like these grew in number over time. Until the emergence of Pauline Hanson, it had not dawned on the political party system that racism inherent in public policy was a vote winner. John Howard realised that he could leverage refugees to acquire political power, which he did as a boat named the Tampa approached Australia. In particular, his use of the meaningless phrase “illegal immigrants” helped reframed the public debate to John Howard’s advantage in August of 2001.

The Pacific solution.

The Pacific solution followed in September 2001 as Howard opened offshore gulags on Christmas Island, Manus Island, and Nauru. After Howard lost government to Kevin Rudd, that new government closed them down. When Rudd lost leadership to Julia Gillard, she reopened them, and once Tony Abbott became PM, he massively escalated the usage of offshore detention.

On his ascension, Malcolm Turnbull did little to change anything by way of policy; he did allow Morrison and Dutton to leverage legislative control of these gulags. The relish with which Dutton justifies the Government’s actions on Manus beggars belief. Given that even the vaguest sense of decency would suggest, “deterrence” ought only to be addressed, at least under the pretence of regret.

Drowning in moral ambiguity.

If we did in any honesty, believe that preventing “drownings at sea” was a moral imperative, then indeed we would be doing what is being done privately by individuals with large boats in the Mediterranean Sea. We would be sending boats to rescue these people, rather than stopping their boats, turning them around and returning them to danger, which is what the Navy now does to prevent “drownings at sea”.

We should also most certainly be addressing the issue of why such people have a well-founded fear of persecution. One so strong, it leads them to seek protection on foreign soil in the first place. We would be spending money at the UN addressing the veto factor or refusing to engage in the sort of bombing and attacks on overseas middle-eastern targets that create push factors that generate asylum seekers.

The notion of leveraging human beings to achieve an end to stop the boats and prevent deaths at sea is comparable to the tactics of hostage-takers in the 1970s. Our government is holding an innocent population hostage to achieve a goal at which they are, evidently, unsuccessful. Claims of having stopped the boats have turned out to be exaggerations or spin. Boats filled with refugees seeking asylum are still “setting sail” to come to Australia as recently as last month. The illusion, however, created and maintained by the government’s response, is to either intercept the boats; pay off the “captains” to turn the boat around; or simply to declare that successful arrivals – when they do arise – don’t count as “arrivals“.

The End – does not justify the means.

The end is not justified by whatever means are applied to achieve it. Instead, it’s the acts of compassion that define a civilised society, when they are brought to bear as the means to address an issue and achieve a goal with justice. And that, Mr Peter Dutton, Mr Malcolm Turnbull, Mr Jeff Sessions and Mr Donald Trump, is something which benefits all members of a community, old and new, and which has never become outdated.