Menzies vs Chalmers

Robert Menzies boldly boasted of £120,000,000 budget deficits in August 1962, as emphasised in Gareth Hutchens’ article in the ABC during the Pandemic, headed “Unlike today’s Liberals, Robert Menzies boasted of delivering large budget deficits“. In contrast, Labour Treasurer Jim Chalmers boasted of delivering consecutive budget surpluses in September 2024. This radical shift in perspective occurred in the late twentieth century, due to the transition from Keynesian economics to Friedman’s monetarism and neoliberalism, which Thatcher and Reagan endorsed. The Thatcherite-originated misinformation that fills the media and public discourse suggests that the Government is like a household and must balance its books. The household analogy as a perspective on federal monetary systems lacks any correlation with national accounting book records. It fails to appreciate the two-tiered monetary system, which no business emulates. The closest parallel I can imagine to a two-tiered system is a company keeping two sets of books: one for the tax authorities and one for the investors. Even then, it is not even a decent approximation. The press and public were not always so uninformed about why it matters or who has the proper perspective: Menzies or Chalmers? The contemporary view primarily focuses on the significance of public debt, while private debt is considered a matter of individual concern, not national.

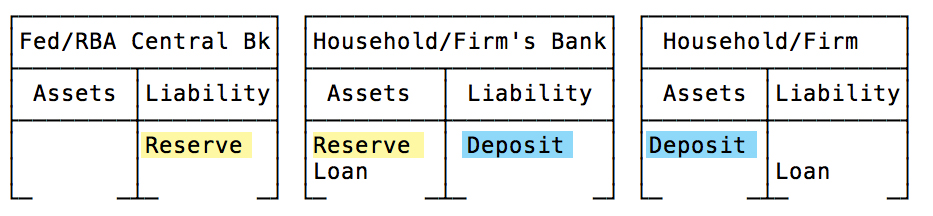

Understanding money flows requires understanding the distinction between the nature of Central Bank reserves, which are exclusive to banking, and deposit money in private banks (and cash) circulating in the economy for the private equity/credit of firms, states, municipalities, and citizens. The essential distinction is to which institution the liability for “money” is due. Bank reserves are the Central Bank’s liabilities, while deposits from corporations, states, municipalities, and citizens (both foreign and domestic) are the liabilities of private banks. Economists often confuse the two-tiered monetary system, in which only Banks can hold reserves, with the economy’s money supply. They rarely discuss money in terms of liabilities because accounting is not an orthodox economist’s discipline. Despite this shortcoming, the Bank of England has made efforts to educate economists, the media and the public.

Framing the question of who held the valid perspective, after a historic Labour victory, creates a challenging choice between a conservative leader and a progressive Treasurer. Many an article or social commentary uses Chalmers’ surplus as proof of Labor’s economic competence, but conveniently forgets that the Liberal’s John Howard government also generated public surpluses. This is an emotional challenge for progressives and conservatives alike, who contend Margaret Thatcher’s assertion that the government has no money of its own is correct, and it all belongs to the Taxpayer.

The Two-tiered Monetary System

Today, there is a lot of talk about “balancing the budget” and “fiscal responsibility,” and despite the Hudson Institute’s argument that it is a myth, even their claim misunderstands. Typically, comparisons are made between the federal budget and household or business budgets. While often repeated, this analogy is flawed even though endorsed by most orthodox economists. Herein lies the reason for recognising that modern economies are two-tiered, as accounting reality establishes that reserves are distinct from privately banked money supply.

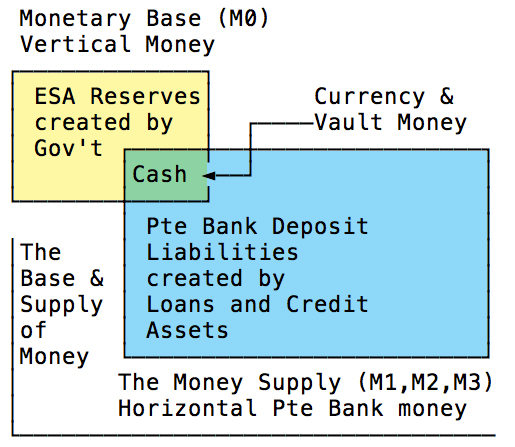

Wall Street primary dealers, mandated to buy government bonds to underpin US Treasury auctions, know that central banks can manufacture reserves at “whim”. Reserves are the Central Bank’s liabilities and are only distributed via accounts at the central bank to the registered private banking system. These banks all hold accounts at the Central Bank containing what is referred to as “M0” money or “vertical money”. This is independent from the rest of the economy that hold deposit accounts at private banks that is known as “M1” money or “horizontal money”, in the finance industry. The Australian Central Bank’s computer (the RITS system) stores reserves as computer entries. Vertical money moves between bank accounts with the central bank, and deposits can be moved amongst private accounts within the Private banks. But reserves and private deposits do not mix. Banks use reserves to pay for movements of money in the second tier of the monetary system (i.e. deposits in private banks). Governments use reserves to pay banks to deposit money into a person’s account for — say for example, a welfare cheque. Banks, pay other banks with reserves but they can not utilise reserve “money” to buy goods and services or earn interest outside the banking system. If you take out a loan from a bank that creates a deposit account with your bank but it needs to “travel” to another bank to pay for a house, for example, then the “travel” is done via the reserves, not the deposit. The Federal reserve’s function is to facilitate the transfer of account balances between banks which then are reflected in deposit balances of households and firms. To illustrate this two-tiered system as accounting records for the entities concerned.

Central Bank reserves are their exclusive liabilities, and deposits are the exclusive liabilities of private banks. Never the two will overlap, except for the exception of printed money. Every banknotes – foreign and domestic – in your possession tells you which central bank hold it as as its exclusive liability. To issue notes at a private bank, that bank must surrender its equivalent value of reserve balances to be issued that cash by the Central Bank. None of it says it is the property of or liability of the Taxpayer, no matter what any media, or neoliberal politician says otherwise. To be the printed creation of or property of the taxpayer and to be passed off as the liability of the Central Bank is a criminal offense in every country on Earth.

Reserves are utilised to facilitate all financial transactions between banks, including government expenditures, and taxation, as well as the circulation of physical currency notes and coins. To illustrate the relationsip by way of a Ven diagram:

The real source of Currency.

Allow me to use a personal anecdote using my father’s wallet to explain monetary origins. I remember his wallet filled with Australian pounds, shillings, and pence. However, my father began using Australian decimal currency in 1966. As a child, I loved collecting obsolete coins, but I don’t know what happened to my collection across multiple house moves. No decimal currency was printed or supplied by the taxpayer. The government has to issue it from scratch (irrespective of what exchange they provided for one’s pounds, shillings, and pence), like any other currency in the globe. Every Australian note you carry reminds you it is the liability of the RBA. In Australia counterfeiting is a federal violation punishable by up to 14 years in prison for individuals and fines for corporations, it is and never has been “taxpayer money”. Perhaps we should lose the “taxpayer’s money” narrative.

The Reserve Bank issues Australian currency, not domestic taxpayers, not China,n not the US, or any other trading partners. All currencies today are issued by governments through the Central Bank they created as an act of legislation that is the bank of Government no matter what legislative illusions of independence each maintain.

First premise: The citizens of a monetary sovereign country are the primary users of the currency, and the Government is the issuer of the currency. That status is the primary distinction that matters most when understanding the fundamentals of money.

Exchange Settlement

“Reserves” as Central Bank liabilities are what modern banks need operate and are managed in the “Exchange Settlement system” (ESA) in Australia. The ESA runs on the RITS system. In 2001, my colleagues and I in the RBA’s technical computer department rebuilt the ESA monetary system’s on an Alpha VAX/VMS OS computer system to reverse the Reserve Bank’s outsourcing of management of the RITS system. Besides providing operating system experience as a former Digital Equipment (which initially made VMS systems) employee, I personally redesigned the RITS system’s operations and inhouse user security Interfaces in 2001.

Bonds: Long-term Deposits with the Government

Government deficits are the difference between spending and taxes. It is a difference not a debt but that difference is covered by the sale of Government Treasury securities/bonds one reason of which is reminiscent of the era before 1971 when monetary systems were backed by the value of precious metals (i.e. gold). Not as necessary to do in the era of fiat currencies. Nevertheless, we sell bonds and incur an interest debt. Government security sales are an asset swap of money for an interest-bearing “note”. The Australian Treasury issues these, essentially, promissory notes for sale, and the Reserve Bank pays the interest debt (coupon rate) when due. Treasury securities are like savings accounts with the Government. Operationally, Bonds are similar to lending cash to a bank for a long-term deposit to secure interest payments, except that investors lend their money to the Treasury for a bond that bears interest. Investing in bonds tends to be more profitable than long-term deposits in banks. That interest expense is what we refer to as the “government debt”.

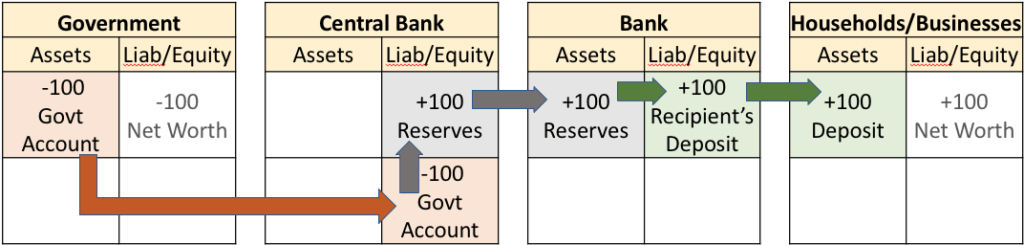

Bonds like Taxes, absorb money from the economy and dampen demand for goods and services. Bonds are although assumed “to pay for” government deficits created by government spending. That spending creates a private sector surplus whether it is for infrastructure, education health care, subsidies, transfer payments of wages for public servants. The accounting flow for spending is as illustrated:

Second premise: The government’s deficit creates a private sector’s surplus or increased the net worth of recipients. It isn’t a loan, it is a payment, and it is not expected to be returned except where taxes are applicable.

Grandchildren’s debts.

Popular economic folklore asserts that government deficits are disadvantageous for households, and to add emotional weight, they are nefariously framed as a debt your grandchildren will owe. That framing is perfect for fostering debt fears in parents. in reality the Government’s deficit increases the net worth of the household, as demonstrated by following the accounting transaction between institutions.

Buying a bond, creates a deficit in the buyer’s accounts and a surplus in the Treasury’s reserve accounts. Banks, individuals or businesses give their money to the Government in exchange for bonds. These bonds earn interest, which is the debt the Central Bank pays. When the bond matures, the Reserve Bank reverses the asset swap and the money originally paid for the bond is returned like a banks does for a long-term deposit. Because Bonds are transferable, the whom, that is paid might not be the original person/bank/corporation, but that entity will have paid for the value of that transfer.

Your grandchildren will never have to pay the interest debt of a bond; only the Reserve Bank is responsible for that. The same bank that issues the State’s currency. The Reserve Bank creates reserve “money” using keystrokes in a computer system called RITS and pays the interest on the bonds. In fact, as an investor, you can leave bonds to your grandchildren as Government Securities are transferable, which would be a bonus, not a debt. So, not a burden to your grandchildren, so perhaps we can also lose that narrative.

Third premise: The “borrowing” of the Government to cover deficits in spending is an asset swap with the private sector that drains money from the private economy and “lends” it to the Government for its central bank (which issues money) to pay the interest on bond maturity later. Every central banker involved in monetary operations understands that it is their job to generate the money the Government spends first into the bank accounts of its citizens or firms.

Cash, Loans & Spending

When government spend it involves creating the reserves it needs to transfer to the balances of private banks. The bank that receives the reserve balance, and credits the allocated recipient’s account with the private bank. The accounting transaction is the same if it is welfare cheque, a bond interest payment, or a subsidy to a fossil fuel company or to pay for excessively expensive AUKUS submarines. When these funds aren’t available because the government decides to spend less than it taxes (known as a government surplus),the money supply shrinks. The citizens in an economy may decide it wants a greater money supply, in which case consumers borrow from banks. Private banks, not the Reserve Bank of Australia, are liable for “M1 money” which they supply as deposits in customer’s accounts when they take out loans. The only role the Reserve Bank’s reserves play, is to transfer these loans between banks, only where that is required. Again, it is encumbent on the Reserve Bank to ensure there are enough reserves available to banks, to facilitate these transfers, in which case the reserve balances are added or subtracted from, as is required. As an example of such substractions, taxes paid reduce the balance of reserves held by banks as it reduces money in the economy but adds to the Official Public Account (OPA) of Treasury. It is no longer part of the private sector. In essence, it’s deleted from the economy.

Accounting summary

So, if one might summerise the transactional movements that affect the accounting balances of the two-tiered economy of public and private monetary systems, with particular reference to how these transactions affects the Government reserve accounting balances, it would appear as follows:

(1) Taxes drain money from the economy but add to the reserves in the OPA account.

(2) Government spending drains money from the Reserves but creates a surplus in the private economy.

(3) Treasury’s bonds add money to the reserves but drain money from the private economy.

(4) Debt servicing (interest on bonds) drains money from the reserves but adds to the private sector.

(5) Printing hard currency reduces banks’ reserve accounts and the Central Bank reserves. It supplies hard currency to the citizens of the economy via the private banks.

And finally – and this is where Menzies understood what Chalmers seems oblivious of:

(6) Surpluses mean taxes (drains from the private economy) are larger than spending (creating money for the private sector), and so they drain money from the private sector and add to the Central Bank reserves. The net movement of accounting funds is a reduction of money in the private economy.

So, where do citizens turn when the Government restricts the money supply by running a surplus? They go to the Banks and loan money!

And what happened when Howard had a surplus? The same thing happened when Chalmers had a surplus.

What happens to private debt in the economy? It usually increases.

Did that happen under Howard and Chalmers’ surplus regime? Yes.

Final Premise: Deficits put money into the private economy, and Surpluses take it out. However, private banking for the public is a separate set of financing, distinct from the Bank’s reserve account provision.

So, Menzies boasted about deficits because he supplied more money to citizens. On the other hand, Chalmers’s boasting about surpluses means he is pushing citizens into higher private debt who do not have sufficient savings to weather the financial depletion brought on the inflated costs of living, because he is draining the private economy of economic resources.

References

- Babcock, C. (2007, November 2). VMS Operating System Is 30 Years Old; Customers Believe It Can Last Forever 2 | InformationWeek. Retrieved from Informationweek.com website: https://www.informationweek.com/software-services/vms-operating-system-is-30-years-old-customers-believe-it-can-last-forever-2

- Collyer, D. (2014, October 15). Australia’s Addiction to Private Debt. Retrieved from Prosper Australia website: https://www.prosper.org.au/2014/10/australias-addiction-to-private-debt/

- Hewett, J. (2024, September 30). Why Jim Chalmers wants to boast about his budget surplus. Retrieved from Australian Financial Review website: https://www.afr.com/policy/economy/why-budget-surplus-is-up-up-up-20240930-p5keli

- Hutchens, G. (2020, August 29). Unlike today’s Liberals, Robert Menzies boasted of delivering large budget deficits. Retrieved from Abc.net.au website: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-08-30/liberal-party-of-robert-menzies-proudly-delivered-large-deficits/12609876

- Kane, T., & Hubbard, G. (2012, August 24). The Myth of the “Balanced Approach” to Fiscal Policy. Retrieved from Hudson Institute website: https://www.hudson.org/economics/the-myth-of-the-balanced-approach-to-fiscal-policy

- Lavorgna, J. (2023). US Macroeconomics The Fed Just Did Massive QE. Retrieved from https://www.smbcgroup.com/americas/getmedia/527d4204-cf36-4e03-8453-9ffc94ad5cf2/The-Fed-Just-Did-Massive-QE-Mar-17-2023-NCFD.pdf

- Mcleay, M., Radia, A., & Thomas, R. (2014). Money Creation in the Modern Economy. The Bank of England. Retrieved from The Bank of England website: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy

- Murphy, R. (2020). Tackling the idea that there is only taxpayers’ money – because that is completely untrue. Retrieved from Funding the Future website: https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2020/11/23/tackling-the-idea-that-there-is-only-taxpayers-money-because-that-is-completely-untrue/

- Murphy, R. (2022). The double entry behind the money creation in the central bank reserve accounts. Retrieved from Funding the Future website: https://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2022/06/21/the-double-entry-behind-the-money-creation-in-the-central-bank-reserve-accounts/

- Nuveen. (2024, December 2). Private credit continues rapid expansion. Retrieved from Australian Financial Review website: https://www.afr.com/companies/financial-services/private-credit-continues-rapid-expansion-20241128-p5kuao

- Reserve Bank of Australia. (2016, February 6). About RITS. Retrieved from Reserve Bank of Australia website: https://www.rba.gov.au/payments-and-infrastructure/rits/about.html

- Schumm, T. (2025, February 2). Primary Dealers’ Role in Stabilizing the US Financial System. Retrieved from CGAA website: https://www.cgaa.org/article/primary-dealers

- Wray, L. R. (2014). Central Bank Independence: Myth and Misunderstanding. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2407707